Dov Spolsky: My first 90 years

Dov Spolsky: My first 90 years

Professor Dov Spolsky was a socio-linguist of international renown and an expert in the revival of endangered languages. In his work he helped in the revival of Te Reo Māori, Hebrew and Irish Gaelic. He wrote this biographical piece for Jewish Lives on the occasion of his 90th birthday in February 2022.

The Greens (mother’s family)

The Greens, (London-born Mark, Albany-born Anna Zelda, Wellington-born Ben, and Bournemouth-born Ellen), returned in 1922 from London where they had been stranded by the Great War, and 12- year-old Ellen became a pupil at Wellington Girls’ College.

The Spolskys (father’s family)

Born in Kremenchug, Jacob Spolsky, (earlier Schpolski, from Shpola) and his wife Esther Nemitz were in Glasgow by 1890, where Hyman Harry was born in 1896, Choony Aby in 1898 and Julia in 1900. Hymie and Abe went to Clyde Quay school. The family moved to Edinburgh for a few years and Jacob sailed to New Zealand on an assisted passage in June 1906, followed six months later by his wife and children. Esther died in 1918 and Jacob in 1934.

In December 1930, my father Abe wrote to his Aunt Fanny to invite her to his wedding planned for 4 February. He was happy that a sweet and charming girl had been brought into his life, who will ‘uphold the worthy traditions that she possesses the tender endearing qualities of my dear mother and that she is worthy of bearing her name. I get very sentimental these days, but you must bear with me because I am very much in love’. They had not yet found a suitable place to live. Everyone seemed very pessimistic those days, so anyone ‘who can have the wherewithal to sustain themselves, that person should be content with his lot, little though it may be’.

Abe Spolsky and Ellen Green were married in the new synagogue on The Terrace on 4 February 4, 1931, presumably by Isaac Van Staveren , son of Rabbi Herman Van Staveren who died on 20 January. Reverend Pitkowsky who had been the assistant minister died ten days later. The newly married couple lived for a while in the block of flats on Brooklyn Road built by Mark Green, but soon moved into the house ‘Annamark’ which Mark had built alongside. Abe continued to work at the Municipal Milk Department.

Birth 1932

I was born a year later, on 11 February 1932 in the Willis Street Obstetric Hospital, operated by Dr Louis Levy and used by most members of the Wellington Jewish community. I was presumably a ‘Plunket’ baby, taken regularly to Plunket rooms where mothers were informed of hygiene and mother craft, a movement which let to New Zealand having the lowest infant mortality in the world. We had at that stage a maid, a young woman from a country home, who slept in the box room, which I occupied for a while and where later Uncle Hymie slept. With barely enough space for a single bed, perhaps it was intended to store boxes.

We had a dog, Scamp, of whom I have two memories: I remember or was told that he accompanied me when I crawled out of the house and up the hill; and he was run over by a car when I was quite young. Later, I had budgies.

I use the first person because of the various names by which I was known: Bernard, (as a child and professionally), Barukh in synagogue until I discovered I had been named Barukh Yehudah, Dov in the youth movement and the Israeli army and by my wife and social friends. And later, Dr or Professor or Dean Spolsky.

Ellen Green and Abe Spolsky, Days Bay, Wellington, 1930.

Baby Dov enjoying the Wellington sunshine.

Dov and friend with Scamp the dog.

Brooklyn School 1938-1944

At the age of four, I went to a local kindergarten where I became friends with Harold Gordon and a year later we both started at Brooklyn School, which was about 15 minutes’ walk from our home at 4 Brooklyn Terrace. The shorter route went over a dirt path which went up a hill; a road then led down to the Post Office, and the school was a few minutes on with its entrance opposite the Public Library. I worked as a telegram delivery boy a couple of summers while I was at high school and borrowed books from the library all during my elementary school days. One memory from school was the day that, alarmed by the Japanese threat, we had our first air raid drill – it must have been in 1941 or 1942 after war with Japan started. We were given small squares of rubber to clench between our teeth if there was bombing, and the school was marshalled and marched to a nearby clump of trees. Packing up and walking there took quite a while, and the story in the local paper, Evening Post, that said we were in shelter within ten minutes usefully destroyed my trust in newspapers.

On the night of June 24, 1942, a major earthquake centred in Masterton also damaged many buildings in Wellington, including the brick building at Brooklyn School, which could not be used for some time after that. That year I was in Standard 5, with my closest friends Harold Gordon and Ronald Gair, the son of the headmaster. With a spare classroom and a spare teacher, the headmaster selected a small number of pupils to be moved ahead and we were given more advanced teaching. Some of us then skipped Standard 6 and were ready to go on high school. My most memorable teacher was Mrs Hebley, who taught me at least two years running and whom I visited regularly later.

My friend Harold did not go to high school, but joined the merchant marine, ultimately becoming a captain and when he retired a harbourmaster. We discovered each other again a few years ago; he was living on the Gold Coast south of Brisbane.

Wellington College 1941-1948

I started at Wellington College in the last year of the war and was placed in the 3A, the top third form. There was a new curriculum in place, so that we had a single class in General Science, (replacing Chemistry and Physics), and in Social Studies, (replacing History and Geography). Other subjects were English, French, and Latin. Some boys took Mathematics instead of Latin. An effect of the war, one of our teachers was a woman.

I was also a pupil at the Hebrew School: we had classes after Sabbath services and on Sunday morning. The ministers were Rabbi Katz and Reverend Kantor, the latter also tutoring boys for bar mitzvah. The headmistress was Avril Boock, who also started a youth group where my name ‘Dov’ was selected. My bar mitzvah was in the last year of the War; we had a week of army cadet training in February so that during the week we were wearing heavy serge uniforms. For the bar mitzvah, I had my first suit with long pants. The main celebration was in the synagogue after services, but there was also a small party at home. Because of the war, it was hard to get the required whisky and beer, and there were no fountain pens available for presents.

I stayed in the A stream all through high school. My closest friend was Douglas Gray, who was later dux (top student). After finishing his MA at Victoria University College with me, he went on to Oxford where he eventually became Tolkien Professor of English. In the sixth form, I was placed in 6A Lower, the first of a two-year program for the University Scholarships Examination and was given a ‘balanced’ program of English, French, Latin, and German. There were a dozen of us in the class, and we later produced six university professors, one doctor, one bank manager and a Governor General.

The photo is from our fortieth anniversary ‘old school reunion’ dinner at Government House in 1988.

Ian Anderson worked in banking in Australia and New Zealand and played a role in computerization; Don Brasch was Professor of Chemistry at the University of Otago; J. C. ‘Snow’ Burnett became a high school teacher and principal; Tommy Farrar was a doctor and President of Royal College of General Practitioners; Douglas Gray became Tolkien Professor at the University of Oxford; Michael Hardie-Boys was judge in the Court of Appeals and then Governor-General of New Zealand; Arch Matheson was Professor of Physical Chemistry at University of Otago; Graham Patchett was an industrial chemist at Mobil in New Jersey; Bruce White became Professor of Physics at University of British Columbia; and Douglas Wright was chief scientist for the Ministry of Research, Science and Technology and head of the Meat Industry Research Institute. I have no information about David Melvin.

I played hockey, but in a low ranked team. I was active in the Jewish community as a leader of Habonim, a Zionist youth movement.

My week during the time I was at college was fairly standard. Monday to Friday, I would walk to school - about half an hour, going through Wellington Tech, past the Dominion Museum and the Basin Reserve, then up the driveway. School started with an assembly, but the half dozen Jewish boys stayed out during prayers and the hymn, coming in for the headmaster’s talk and the announcements. I brought sandwiches for lunch which I ate with friends. There were sports, (hockey for me), one afternoon a week; another day, we wore uniforms and had cadet drills and training in the afternoon. In my last two years I was a librarian so I ate lunch in the back room and spent half an hour or so after school on duty. I usually took trams home – one to Perret’s Corner in the middle of town, and one from there to Brooklyn. Friday night we made kiddush and usually ate fried fish. Shabbat morning, I walked to shul, often with my father, with Hebrew School after. In the afternoon, I played hockey in winter. Sunday morning was Hebrew school and in the afternoon was a Habonim meeting.

Some of our teachers were memorable. Mrs Turner taught us Latin for one year, but she was succeeded by Bernie Paetz, who sat on the heater, and taught us to parse and then carefully translate word by word. Our first French teacher was ‘Ducky’ Wells, who took us through phonetic script to real French. He was succeeded in the sixth form by Norman McAloon who was the second senior master; he introduced us to European culture and was easily diverted to talk about his travels to France. He also taught us German, and once or twice Latin, where he insisted that we keep reading a passage until it made sense. He was appointed a master at the College in 1930, with MAs in French, Latin and German and became head of languages in 1945, First Assistant in 1950, and Deputy Principal in 1964. In the fifth form, our science teacher was ‘Jimmy’ Cuddie , senior master, whose tests combined oral individual questions (‘naught – next’ if you were wrong) and written questions. Our English master was ‘Q’, Leslie Quartermain who had us read complete literary texts in our sixth form years and who we understood was an Antarctic explorer. He oversaw the school library, and on occasion sent one or two of us to secondhand book auctions with marked catalogues. Quartermain (1895-1973) served in the Great War in France as a medical orderly which he never mentioned but this explained his reaction to war poems, (his letters home are kept in the Turnbull Library). He taught at Christchurch Boys High School for eight years and was head of the English department at Wellington College from 1930-1956. He was founder of the New Zealand Antarctic Society and edited its journal from 1950 to 1968. In 1959, having retired from teaching, Quartermain joined the newly established Antarctic Division of the New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research as Information Officer, a post that gave him opportunities for historical research and writing, (Quartermain, 1971). He at once began work on chronicling the history of the Ross Dependency. In 1967, he was awarded the MBE for his outstanding contributions on Antarctic affairs.

My time at Wellington College was influential; it set my course towards humanities rather than sciences and provided me with a set of friends with whom I have tried to stay in touch.

Victoria University College 1949-53

After three years of classes and final examinations, (School Certificate, University Entrance and University Scholarship), I went on to Victoria University College, (now Victoria University of Wellington) and enrolled as major in English and French. English I continued until I completed a BA and an MA (with honours); French I dropped after two years, unimpressed by the non-francophone teachers, (the professor was a tramper). One year I was secretary of the Socialist Club, another I was a well underqualified member of the College hockey team at the New Zealand Universities tournament in Dunedin, (the better players were on tour in Australia). During this time, I continued to be an active leader of Habonim and to play hockey. My closest friend was Doug Gray, but later I also became friendly with Bryce Harland, who later went on to be NZ Ambassador to China and New Zealand High Commissioner in London.

Many of my friends in Habonim went to Hachshara in Australia and on to kibbutz in Israel. I was persuaded by my family to be more cautious, so after completing my MA I enrolled in a secondary school teachers’ training program in Auckland, living with aunt Julie, uncle Mendel and Cousin Lionel, (Ray was in Medical School in Dunedin).

It was a good year, my first away from home and fairly relaxed after the pressure of school exams. We complained to the director of the programme, a former senior officer in the Air Force about how easy it was: he pointed out that an air force plane flying overhead probably was costing the government more than our programme and our bursaries. The most useful class was French, where we were given training in how to teach the first-year programme. Auckland also was a welcome break – a different shul, much warmer weather, beaches, and sailing. A different routine too: Auntie Julie helped her husband in the pharmacy, but came home in time to serve a meat and potatoes dinner.

Gisborne High School 1953-4

I then looked for a job, which had to be in a country school in order to get certified. I became an assistant master at Gisborne High School, hired to teach English, French, and Social Studies and to become coach of the school senior hockey team. For two years, I was also a master in the Boarding House where I lived. This, and the hockey team, gave me my first serious connection with Māori pupils, some of whom I also taught.

My closest friend was the art master; we went to movies together once a week. I also biked quite a bit. Only in my second year did I realize how bad a teacher I was in the first year. My experience with Māori was important – when I discovered that the pupils who said they spoke Te Reo at home wrote better English than those who said they spoke English, it launched my interest in bilingualism that drove a large amount of my later scholarly research.

Caulfield Grammar School 1955

By the second year, I was ready again to make Aliyah, though my father continued to complain that our generation leaving would doom the community. But again, a visit by my uncle from Melbourne supported the family pressure to take it slowly. So, I planned a year in Australia, was appointed to a job at Caulfield Grammar School in a Melbourne suburb, and once again lived in the boarding school as my remarried uncle Ben was off on a six month’s world tour. When he got back, I would occasionally spend a weekend with Ben and Edith in their house in the mountains, eating dinner with them and friends in a small local restaurant.

Teaching was uneventful. I spent the first Seder with my family, and the second with the German master, a refugee and his family who knew much more. I bought a small secondhand car and made two major trips. The first holiday I drove north, spending a few nights in a motel at Surfers Paradise where my uncle Ben later built the first multi-story apartment house, and got as far as Brisbane. The car just made it back. At the end of the year, I went with a group of teacher colleagues by train to Alice Springs in the Northern Territory and learned about heat, dryness and beer. I flew back, (my first flight), to be in time for my cousin Geoffrey’s wedding in Melbourne.

Shortly after, we sailed, (Geoff and Pauline on their honeymoon and me on my way to Europe), on the Castel Felice, a ship used to transport Italian immigrants to Australia, that offered fares that students could afford, (no fresh water for showers, and my berth in a large dormitory). But the food and wine were Italian, and the ship stopped at attractive ports – Auckland, where my family came to say farewell; Fiji for my first taste of the Pacific to which I happily returned in later years; Tahiti for my first francophone territory and later an ideal place to stop off when flying to or from New Zealand; the Panama Canal; Madeira; Lisbon; and finally, England. Our days on board were relaxing; up in time for a drink before lunch; an afternoon nap; quiet drinking into the night.

The Royal Russell School 1956-7

London was a surprise, though from Monopoly I had learned all the street names. I stayed at a hostel while looking for a job, and tried relieving teaching for the London County Council, driven off by a class of Greek and Turkish Cypriots who fought all the time. I bought a scooter and having found a job as assistant master in a small public school just outside London, set off on a trip to the Loire region to brush up my French and visit chateaux until the start of term.

The year in England was an opportunity to learn about English accent and dialects. Royal Russell school, a nineteenth century establishment for the orphaned children of warehousemen, drapers and clerks was outside Croydon and single sex, the girls’ school being separate. The boys came in quite young, speaking lower class regional dialects which they kept up in the dormitories, but they had moved to standard RP in class by the time they were in the upper school. There were several ‘houses’; my room and house duties were in the old school, my bathroom said to have been used by the Kaiser on visits. There was a small staff room with a miniature billiard table, and a great view down to a nearby suburban town. Breakfast and lunch we ate at high table in the dining hall, each master reading his own newspaper unless the bishop was visiting for communion. I ordered the Guardian, which sometimes was delayed in the fog. There were prayers before morning school and one afternoon was for cadets and another for sports. Before supper, which the resident masters ate together, we would regularly walk down to the local pub – best bitter in the summer, beer and Burtons in the winter. I made friends with another master, Andrew Foot, who lived with his family; our relationship lasted as long as he was alive. He visited us in Jerusalem and confessed that he had been on a Royal Navy ship that directed Jewish immigrants to Cyprus. We visited them in Cornwall years later.

Again, I took a major scooter trip during the holidays, essentially following the coastal road to circumnavigate England and Scotland. Highlights include a week or so in a boarding house in Whitby, where there was an East End Jewish tailor who made suits for Newcastle gangsters and coming down through Wales where the pub conversation turned to the disputed try in the 1907 All Blacks match.

Dov visiting his good friend Doug Gray, Oxford, 1966

Dov with two of the senior boys at Gisborne High School, all in their Sunday morning suits.

Teaching at the Royal Russell School gave Dov an opportunity to explore the UK.

Aliyah 1958

While in England, I spent a weekend with a Zionist group in preparation for aliya, and at the end of the year set off with the group for Israel. We took a ferry to France and a train to Marseilles, then sailed for Haifa without our luggage because of a rail strike. I bought some lighter pants and a shirt in Naples, for I was dressed for cold weather in London. And it was hot in Israel. Without luggage, formalities were fast, and I was advised to take a sherut – my first experience of this Israeli method of travel. I was dropped at the Kfar Vitkin intersection and got a tremp from the main road (the coastal road was built many years later). At the moshav centre, I was fortunate enough to find a donkey and cart heading for Beit Yanai, where the Finklesteins lived with their lul in the centre of the settlement, (they built and moved to their cliff-top house much later). I had known Athol and Olga in Auckland, and they had invited me to stay while waiting for the ulpan to start. I made a short trip to Jerusalem to see another NZ oleh, Shlomo Ketko, and to Kibbutz Yizre’el where other New Zealanders were arriving. For Yom Atzmaut, I took Mrs Astor, (the Auckland rabbi’s wife), to the IDF parade.

Once it was time for the ulpan to start, I moved to Bat Galim in Haifa – I had found my missing luggage by then. The course at the ulpan lasted five months and classes were all morning. I slept in a large room with several other students – I recall Bernard Turner from England and one-legged Nandi from Yugoslavia. My ability to read Hebrew placed me in the second to top class; other students there were women from Latin America and a Tunisian teaching in an Israeli village school. Our teacher who spent much of his time on the Zionist ideology that was the main ulpan curriculum insisted on using only Hebrew; he kept explaining new words in Hebrew until the class passed a translation around in half a dozen languages.

During the ulpan, I spent a shabbat with Frank Auburn in Kibbutz Yizre’el. After shabbat, I walked a mile or so to visit my Tunisian fellow-student in a nearby moshav. I was impressed by the language situation. When I arrived only her elderly in-laws were in the house; Arabic speakers, we managed to converse in simple French. My friend had been brought up speaking French and was in the ulpan to continue as a teacher; she spoke French to her seven-year-old son but when they walked across the road to school switched to Hebrew. Her husband had been brought up with Arabic and French and had added Hebrew for his job as secretary for the cluster of three moshavim, one Tunisian, one Moroccan, and one Polish.

The Hebrew University 1959

Towards the end of the ulpan course, I started job hunting, but was told that my Hebrew was too weak for me to be a high school English teacher. However, that year the Hebrew University hired several assistants to teach English as a foreign language. I joined Zvi Jagendoff, (who had made Aliyah at the same time as me); Nelson Berkoff, (who had taught English in the Reali School in Haifa; and Eddie Levenston, (who had planned to be a Hebrew teacher in a moshav), to teach academic English to non-majors.

I shared a rented apartment on Gaza Road with an Israeli radio announcer who had a great collection of English detective stories. I bought a scooter to be able to visit friends in other towns. I started to read applied linguistics but remained amateurish. Towards the end of the year, I received what I later learned was a meaningless letter from the dean firing me, (a method of avoiding tenure), so decided it was time to take out citizenship and fulfil my army service requirement.

Israel Defense Forces 1959-60

So, at the advanced age of 27, I set off to be a recruit. I was sent to Bahad 4, where nonfighting troops were trained, and found myself one of the old men, (one Egyptian university graduate, one Israeli graduate of Wingate Institute for Physical Education, and one Moroccan who had been sent back there as a madrich), with two contrasting and conflicting groups of 18 year-olds, half Moroccans and half Poles being trained for the air force; our NCOs were young immigrants. Somehow, I survived, and by never saying ‘I can’t do it’, I was twice selected as soldier of the week and granted leave.

I had given up my share of the Gaza Road apartment but was happy to be offered a bed or a couch in a large house in Talpiot that had been prepared for Eliezer ben Yehuda but never occupied by him. The ground floor had a kitchen with the other rooms set up as a museum, but upstairs there were two bedrooms, a sitting room with a telephone, (rare in those days), and a verandah with a view of Jerusalem. My host was Rolf Ruben, also from Wellington and working in insurance, but the main residents were US college students, one of whom, Rafi Rothstein, was preparing for aliya by struggling to learn Arabic. This was where I often spent my leave on Shabbat; other shabbatot were at Beit Yanai and Kibbutz Yizre’el.

When recruit training ended, I was ordered to report to the Education camp at Machaneh Marcus, on the Carmel range above Haifa, and set off with my kitbag on the back of my scooter. Oh, they said, you are not assigned here: report to General Staff Headquarters in Tel Aviv. I had been interviewed by a senior officer during recruit training but given no idea of my fate. The Matkal occupied a large base in Ramat Gan; I left my scooter outside the guarded entrance and made my way to a small office of the education branch of the Chief Education Officer, (there was no Education Corps yet), where a colonel greeted me: ‘My name is Moshe, what’s yours?’. I was taken next door and given a desk alongside the major in charge of language training; in the next offices were majors in charge of elementary, secondary and geography branches, each with a couple of sergeants or corporals. My major spent most of his time assigning civilian English tutors to officers about to be sent to the US for training. He was also responsible for some Arabic and English courses. As a private, I was sent to sleep in a large dormitory on the base and required to carry out guard duty.

There was a major improvement when I was given a temporary appointment as an officer, after which I was assigned quarters in a hostel for junior officers in Jaffa. Life settled into routine: I’d get up late, buy a fresh bread roll and a yoghurt at a shop nearby, ride across Jaffa and Tel Aviv to the base, spend the day working on an English curriculum, have a midday meal in the officers’ mess, and go back to Jaffa after work for an omelette. There was a movie theatre nearby, with movies dubbed in Hebrew and Arabic and eight other handwritten languages scrolling on each side; Jaffa was a site for immigrant settlement. Life became easier when I started to give private English classes to the officer in charge of motor vehicles; he persuaded the base sergeant-major to drop me from guard and officer duties and arranged for me to get a driving license.

Among my duties was to visit the English programme at an Air Force base in the north, and the teacher, Pinhas, a South African oleh, became a friend. One day he called me, (our only connection was through the army telephone system), and asked me to join him and a friend to take out three visiting American girls. He promised to pay me back the lira he owed me. We met in Tel Aviv on a Wednesday night and could not afford to pay for anything but a coffee, (I didn’t get the lira), so we walked around the town; I am told that I spent some hours talking to one of the girls and offered her a ride to Jerusalem on Friday which she refused. Friday night, I made my way to Jerusalem and as my friend Frank from the kibbutz had a date, I went over to the Goldstein village where the girls were spending their last Shabbat. I chatted for some hours to one of the girls, who I took for a scooter ride in the Jerusalem hills next day and to a play at the YMCA to which Shlomo Ketko, (working at the Jerusalem Post), had given me tickets. That night, I realized that I was in love with Ellen, but she was not ready to stay and marry me. Monday night I came up to Jerusalem again, and persuaded her to leave her farewell party, but not to change her plans. I went back to the army, and she flew home to go to Smith College.

Jerusalem again 1960-61

The army discharged me in time to start teaching at the Hebrew University again. With only Ralph and Rafi left in Beit Ben Yehudah, I moved in for a year of teaching and writing letters to Ellen at Smith. Eddie and I also taught two courses in Tel Aviv and spent much time discussing how to study linguistics. Eddie decided on Edinburgh, but I chose North America; blocked from the US by the low quota for New Zealanders, Canada was the next choice.

Montréal 1961-1964

The promised job in a Montréal high school having disappeared, once again I fell back on a university appointment, this time at McGill University, as a lecturer in English at the College of Education located at Ste Anne de Bellevue, an hour’s drive from the city. Before the school year started, I made a trip to New York to visit Ellen, learning that its residents all considered where they lived, (a friend in lower Manhattan, her parents in Brooklyn, her grandmother on 40th Street, Ben’s sister-in-law on East 70th Street) the centre of city.

Back in Québec, I moved into a dormitory in Ste Anne, my closest friend there just finishing his doctoral dissertation though actually because of committee problems, I finally finished my doctorate before he did. McGill declining to recognize linguistics, I enrolled for a doctorate at the Université de Montréal where a well-balanced team of teachers led by Jean- Paul Vinay sheltered me from the Chomskyan wars just starting to heat up US departments. During the year, Ellen visited occasionally, braving the seven-hour rail trip from Northampton. And I wrote my first academic papers (Spolsky, 1962a, 1962b).

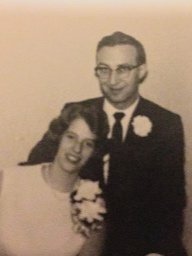

The next year, Ellen switched from Smith to McGill and during the winter break we were married at the family Chanukah party. We rented an apartment in Notre Dame de Grace from which Ellen could ride by bus to McGill and I could drive to the College. We occasionally could afford cheap francophone restaurants and entertainment.

Dov in the IDF

Dov met Ellen in Jerusalem, but she wasn’t quite ready to marry him at that stage.

Ellen and Dov on their wedding day.

Indiana University 1964-1968

I applied for a post-graduate seminar planned for the summer Linguistics Institute at Bloomington and was admitted and offered a lectureship in the newly established department of linguistics. (The seminar led to my first book (Garvin & Spolsky, 1966). Staffed by senior figures from other departments, (Thomas Sebeok and Alo Raun in Uralic, Fred Householder in Classics, Whitehall in English, Carl Voegelin in Anthropology and Albert Valdman from French as chair), I was the first full-time appointment and responsible for English as foreign language, applied linguistics, and an MAT for foreign students. Ellen became a doctoral student in English, one of her closest friends being Golda Werman with whose husband Bob, neurophysiologist, and poet, I started a Jewish minyan that grew into a synagogue after we both left.

Life in Bloomington was good; Ellen was a graduate student and a mother when Avram Joel was born (see photo); a first-class university in a small town, with a music school that offered free programs every night and a weekly opera in the summer. While the department was somewhat dysfunctional, (the deans sent representatives to see that students were not penalised for their linguistic ideologies), there was a weekly linguistic seminar with visiting speakers followed by a wine and cheese party where you could discuss anything but linguistics and Vietnam. When Ellen finished her PhD, it became clear we would have to leave, so I gave up the offer to run a research centre and we both accepted positions at the University of New Mexico, Ellen as assistant professor of English and me as associate professor of Education and Anthropology to which Linguistics was added when I founded the department.

Ellen with Avram Joel when the family lived in New Mexico.

The young family soon returned to Israel.

Dov with Bob Cooper and ‘guru’ Joshua Fishman.

The University of New Mexico in Albuquerque 1968-80 with breaks

Academic life, publication, and Jewish communal activity continued for both of us. The family grew. Our young son was the second to enrol in the new Jewish kindergarten, which we nursed until it became a day school in which his sister too was educated. We taught, travelled, wrote, and published, and tried to return to Israel.

On a sabbatical leave in Jerusalem supported also by fellowships, we met the Fishmans. Joshua was in the middle of a three-year stint there, working on an international study of language planning. There was a suggestion to build a programme in linguistics in the school of education at the Hebrew University, but it collapsed late in the year, sending us back to Albuquerque.

On our return, a suggestion from the conservative rabbi not to worry that Joel was bored at Hebrew school but just wait until he had forgotten Hebrew was the last straw, and together with similarly dissatisfied parents from other shuls, we started the first non- professional Havura which ran weekly services and a school and high holiday services in the university chapel, to which we brought a portable ark for our sefer torah; the ark was made by Neil, an undergraduate who also looked after our children.

I directed a program for Navajo language maintenance and literacy, with government and foundation grants that made it possible to add research assistants and work on the reservation (Spolsky, 2002, 2009; Spolsky & Holm, 1977).

Teaching, research, and promotions continued – Ellen was associate professor in a few years, and I was professor and became Graduate Dean. And we planned to retire early and move to Israel. On our next sabbatical, though, we found the children were happy in the Old City where we rented an apartment and were offered jobs at Bar-Ilan and Ben Gurion universities. (‘We tried to hire you in 1972,’ they told us at Bar-Ilan, ‘but no one told you’.) We accepted Bar-Ilan on condition that there really were jobs, and I was appointed full professor with immediate tenure in the English department, with Ellen also getting a position.

Bar-Ilan University 1980-2000

In 1980, then, we made aliya as a family, moving into one of the last rebuilt apartments in the Old City. It took us thirty years to notice that it was on the third floor, ten minutes’ walk and an impossible staircase from the always crowded parking lot. Our daughter joined a small class of girls in the national religious school, I joined the shul where their fathers prayed, and Joel started a year in yeshiva and then moved to a local high school. Friday night we prayed at the kotel, Joel with the Yemenites and me with the Vishnitzers until Joel went into the army and I joined a Zionist minyan. We made close friendships and arranged a carpool for our three days a week at university.

Both our academic careers advanced, and by the end of our time there, we were the two full professors in English. We conducted and published research, and each ran a research centre that organized international conferences. Sabbaticals, summer and winter breaks were often spent in Washington, Ellen at the Folger Library and me at one of the many linguistic research centres. Our published records grew apace.

As long as my mother was alive, trips to New Zealand made it possible to add research on Māori language revival to my work on Navajo, (Spolsky, 1996, 2001, 2003, 2005), including a visit to the Te Ataarangi hui. (The photo below from 2008 with Dame Katerina Mataira, one of the pioneers of Māori language revitalization.)

And of course, being in Israel added a third interest, (Spolsky, 2010, 2013, 2014, 2018). I was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Letters by Victoria University of Wellington..

Prof Spolsky with Dame Katerina Mataira, one of the pioneers of Māori language revitalization, 2008.

Prof Spolsky was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Letters by Victoria University of Wellington. Pictured here with Ellen (on the right and sister Ruth left).

This interest was broadened to language policy during a visit to Washington, (Spolsky, 2004, 2011, 2021).

A lecture I gave in South Korea led me to involvement with the Asian Teachers of English as a Foreign language, annual conferences there, and co-editing of eight books.

During this time, I was fortunate enough to work closely with two colleagues. Every Friday morning, I would meet for coffee with Bob Cooper who has writing his major work on language planning, (Cooper, 1989); we later collaborated in publishing three books, (Spolsky & Cooper, 1991, 1977, 1978). The photo, taken one Purim, shows Bob and me with our guru, Joshua Fishman.

I also started to argue and work closely with Elana Shohamy and we developed a theory of language policy and a language education policy for Israel, (Spolsky & Shohamy, 1999, 2001). The photos show the research team and Elana.

Dov, Ellen and their family.

Retired - 2000 onwards

I retired in 2000 and continued to expand my research and publication. But the family has become increasingly important – Joel and the startups he has now sold, Ruthie raising five children and her career in logistics, Ellen also retired as professor emerita finding time and attention for me while continuing to write and publish. My nephew Paul and his doctor wife Katy moved their family to Tel Aviv. Abe Sterne who had been a fellow student of Ruthie’s the year we spent at Carmel College in England married Abigail and finally moved their family to Jerusalem. Three grandsons did army service, as had I and Joel and Ruthie and their sister Elisheva. And our great-grandson Noam was born.

References:

Cooper, Robert L. (1989). Language planning and social change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garvin, Paul, & Spolsky, Bernard (Eds.). (1966). Computation in linguistics: a case book. Bloomington, IN.: Indiana University Press.

Quartermain, Leslie B. (1971). New Zealand and the Antarctic. Wellington: Government Printer. Spolsky, Bernard. (1962a). Comparative stylistics and the principle of economy. Journal des Traducteurs, 7(3), 79-83.

Spolsky, Bernard. (1962b). Report of an experiment in programmed learning carried out with graduate students in the summer of 1962. The Bulletin, McGill University Institute of Education, 1-3.

Spolsky, Bernard. (1995). Two Wellington families: Green and Spolsky. In Stephen Levine (Ed.),

A standard for the people: The 150th anniversary of the Wellington Hebrew Congregation 1843-1993 (pp. 271-278). Wellington New Zealand: Hazard Press.

Spolsky, Bernard. (1996). Conditions for language revitalization: a comparison of the cases of Hebrew and Maori. In Sue Wright (Ed.), Language and the State: Revitalization and Revival in Israel and Eire (pp. 5-50). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2001). The relative success of Maori and Navajo efforts to resist language loss. Paper presented at the Third Internat ional Symposium on Bilingualism, University of the West of England, Bristol

Spolsky, Bernard. (2002). Prospects for the survival of the Navajo language: a reconsideration. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 33(2), 1-24.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2003). Reassessing Maori regeneration. Language in Society, 32(4), 553-578.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2004). Language Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2005). Maori lost and regained. In Allan Bell, Ray Harlow, & Donna Starks (Eds.), Languages of New Zealand (pp. 67-85). Wellington: Victoria University Press.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2009). School alone cannot do it, but it helps: Irish, Hebrew, Navajo and Maori language revival efforts. Paper presented at the Visiting professor seminar, Institute for Advanced Studies, University of Bristol, UK.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2010). Conditions for language revitalization: A comparison of the cases of Hebrew and Maori. In Peter K. Austin (Ed.), Endangered languages: Critical concepts in language studies. London: Routledge.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2011). Language policy. In Patrick Com Hogan (Ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the Language Sciences (pp. 421-424). New York NY: Cambridge University Press.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2013). Is Hebrew an endangered language? (in Hebrew). Hed Haulpan Hechadash(100), 3-13.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2014). The languages of the Jews: a sociolinguistic history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2018). Sociolinguistics of Jewish language varieties. In Benjamin Hary & Sarah Bunin Benor (Eds.), Languages in Jewish Communities, Past and Present (pp. 583-601). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Spolsky, Bernard. (2021). Rethinking language policy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Spolsky, Bernard, & Cooper, Robert L. (1991). The languages of Jerusalem. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Spolsky, Bernard, & Cooper, Robert L. (Eds.). (1977). Frontiers of bilingual education. Rowley, MA.: Newbury House Publishers.

Spolsky, Bernard, & Cooper, Robert L. (Eds.). (1978). Case studies in bilingual education. Rowley, MA.: Newbury House Publishers.

Spolsky, Bernard, & Holm, Wayne. (1977). Bilingualism in the six-year-old Navajo child In William Mackey & Theodore Andersson (Eds.), Bilingualism in early childhood (pp. 167- 173). Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Spolsky, Bernard, & Shohamy, Elana. (1999). The languages of Israel: policy, ideology and practice. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Spolsky, Bernard, & Shohamy, Elana. (2001). The Penetration of English as language of science and technology into the Israeli linguistic repertoire: a preliminary enquiry. In Ulrich Ammon (Ed.), The dominance of English as Language of Science: Effects on other languages and language communities (pp. 167-176). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Prof Spolsky wrote this memoir for Jewish Lives in February 2022. Sadly, Prof Spolsky passed away on 20 August 2022.