Shirley-Anne Hodgson: Four Generations, Four Countries

Shirley-Anne Hodgson: Four Generations, Four Countries

Shirley-Anne Hodgson tells the story of how her family left Eastern Europe for new beginnings in South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

by Shirley-Anne Hodgson

Growing up in South Africa with a large extended family I had not felt the need to know my family’s story. Additionally, my mother hadn’t been very forthcoming about who had remained behind when they fled from Lithuania. “What do you want to look for, there is nothing there.”

She had never wanted me to look back, insisting I always look forward. Despite this, I became more interested in exploring my roots, so in 2019 my husband and I travelled to Lithuania. My first impression confirmed her words; the once vibrant Jewish community had been annihilated. Visits to the mass graves in the forest where families were mown down in their thousands were harrowing and as my mother advised, does not bear thinking about.

We visited the charming small town of Salakas (Salok in Yiddish) and saw the beautiful lake just outside the town, where my family would have been able to picnic and perhaps go swimming. In the village centre, the synagogue was gone, replaced by the town hall, in front of which was the town square (empty now), but where a market once stood. Around the square were double-doored homes, which would have been the homes of the Jewish traders; one door was for trade and one for the family to enter and exit. I could visualise the story my mother told, of a goat chasing her from the market. With a brilliant sense of humour my mother would tell us, the goat tried to jump through the window and got stuck: “It was framed”.

I could also imagine my grandfather working as a cobbler, selling his wares at the market. Some of the houses were large and I remembered my mother telling me how she had peered through the windows of the rich people as they ate, hunger gnawing at her stomach. The Nazis and their Lithuanian accomplices destroyed so much of the rich Jewish culture that had existed there, but echoes remain.

My mother’s story did not start in Lithuania. She was born in Simferopol in the Crimea, in the pale of settlement. I presume they were amongst the thousands of Jews deported from Lithuania in 1915 in the wake of the first World War. This is the only explanation I have for why they were in the Crimea and not in Lithuania, where they still had family.

“In the later part of April and in early May 1915, expulsion of Jews was ordered on an enormous scale extending over the provinces of Grodno, Kovno and Kurland…… Jews were deported with sometimes a few hours’ notice, other times a day or two. ……. They were transported in cattle cars, packed like sardines, and those were the lucky ones - the rest were forced to travel on foot.” 1

Then in one of the many ironies the Jews faced, the Lithuanian government allowed them to return in 1920, shortly after my mother was born. Their property had been confiscated during the Russian revolution and amid the fighting between the ‘Red’ and ‘White’ armies, they embarked on a 3-week train journey across Russia, back to Lithuania. My grandmother traded the last of her valuables, a gold necklace, in exchange for a sack of potatoes. Arriving in Lithuania, they moved in with family, but faced poverty and near starvation. Hunger was constant, the local schoolteacher was accused of being a communist and arrested, which ended any possibility of education.

My grandfather (Zalman Sabencer), decided to leave for a better life as there were few opportunities to look after his family. This would allow him to send money home and eventually allow all the family to leave. He left in approximately 1928 and it was not until 1933 that the rest of the family were able to join him, aided by a benefactor from America.

Sadly, I have no idea who this person was and what family I have in America. My grandfather’s sacrifice resulted in his early death as well as the death of his oldest son from tuberculosis, who he had sent for as he needed help. Working as a cobbler, in a dingy basement and sleeping behind a curtain in the same space, would have been to blame for his and my uncles’ poor health. Leaving in 1933, the family narrowly escaped the horrors that would befall the Jewish population that remained behind. My mother spoke of the family being met at the station in Germany and being warned that Jewish families were disappearing every day.

2019 visit to Salakas Lithuania

My grandmother, my mother and four of her brothers. My mother shows her father the watch he bought her for her birthday 1932/1933

My great grandfather, grandfather, grandmother, and my fathers’ sisters: Minnie, Tilly, Nathan Jack, Zalman, Aryeh, Anne, Eva, Netty Levin. The youngest, Rosie, was not yet born.

My father’s family (Levin) came from the town of Rosikis in Lithuania. The family can be traced back to the middle 1700s. The painstaking work of a relative who has compiled the strands of the Levin family, has given me an insight into this side of my family. It would have been the events of the first World War which compelled my father’s family to emigrate to South Africa, rather than be expelled to the interior of Russia. Consequently, my father was born in South Africa one of a family of six, the rest all girls. He was able to benefit from an education that my mother was denied, but as with all other poor Jewish immigrants, earning a living was paramount. This was even more critical as his father had suffered brain damage during an attack at his shop and was never the same.

Compared to their lives, my life in South Africa was uneventful. Our local primary and secondary school were at least 50 or 60% Jewish, and we had no need to socialise with anyone outside our Jewish group. We were also blind to the racial inequality surrounding us.

In her early life, my mother had been a receptionist for a furniture manufacturer. My mother was always very outspoken and told the story of a day when her boss made an antisemitic remark. She got up from her desk, put her coat on and walked towards the door. In dismay, he asked where she was going, to which she retorted that she refused to work for an antisemite. Profuse apologies followed and clearly did not affect my mother’s position, so much so that when he met my father, (my mother’s then fiancé), he offered to set him up in a retail shop selling his furniture. So began the furniture outlet Russell and Company, which would later become a publicly listed company, and which still exists in the name of Joshua Doore, though it has changed hands.

This meant we were able to move from our modest home to a newly built one, when I was 8 years old. I now had my own room after having shared one bedroom with my two older sisters. Again, like other ‘white’ South Africans we employed housekeepers, a cook, a cleaner and a gardener. Our home was a magnet for our extended family, who would arrive at anytime of the day or evening.

We were not particularly observant, but Friday night was sacrosanct, and there was no question of any of us missing the Friday night seder. We also attended synagogue regularly and never missed attending on any of the high holidays. I did not attend a Jewish day school but did go to cheder after my normal school day ended. There I learnt the smattering of Hebrew that I now have. Passover dinner was always memorable. A long table would be set up, extending from the dining room through the doors to the living area of my grandmother’s apartment. The table would be laden with all the traditional Askenazi Jewish foods: gifilte fish; herring of every type: baked, pickled, marinated in a tomato sauce, curried and chopped. Then there was always chicken and matzo ball soup; followed by cholent; kishke (stuffed intestine with a filling made from a combination of meat and meal); chopped liver; p’tcha (a kind of aspic prepared from calves' feet). I was not partial to any of these very foreign dishes and to this day remember them with a particular aversion. My uncle read the service in very broken Hebrew and the service was abbreviated, but there was a sense of tradition and family.

My mother and father, Sarah and Nathan (Naty)

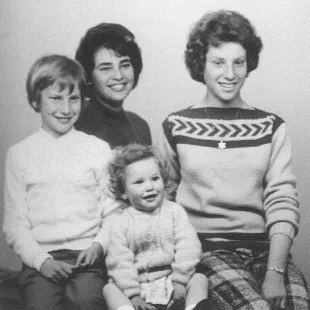

L-R: Shirley-Anne, Joyce, Hilary and centre front, Rene

Married before I even finished my final year at University, I did what most young people in South Africa did and employed a housekeeper. Her story forced me to confront the reality for ‘black’ people in apartheid South Africa. She had been training to be a nurse and sadly failed one year. That ended her chances of a career in nursing and so she became a domestic worker; there would be no second chances. Even getting as far as she did would have been a struggle in a society where educating ‘black’ people was discouraged.

A turning point for me, was when I unwittingly went with her to the local police station to have her pass registered, so she could legally be allowed to continue to live in Johannesburg.

“The pass defines a person's tribe, and thus the ‘homeland’ set aside for that ethnic group - and indicates whether or not that person may reside in a Black township in white South Africa, under Section 10 of the Blacks (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act of 1945, as often amended.” 2

The problem was that under the Areas Act, her tribe was not allowed to be in Johannesburg, and she would have had 24 hours to leave. The police officer had a stamp to that effect poised over her pass. Without a pass allowing her to stay in Johannesburg she could be arrested, but a stamp in her passport meant that her illegal status was irrevocable. I acted instinctively and remember saying, “you are not going to stamp that”, grabbed the pass before his stamp hit the paper and ran. She was waiting outside, and we quickly leaped into my car and sped away. Fortunately, no one followed us, but this meant she still did not have a valid pass and could be arrested any day. This fate was not as bad as the immediate deportation, which would occur with a stamped passport, marking her as illegal. However, there were many evenings when we arrived home to find that she had narrowly avoided arrest for pass violations, by hiding under a neighbour’s bed. The police pass van rounding up illegals was a common and feared sight in apartheid South Africa.

The apartheid system was at its most brutal. The risk of fighting the regime was great and was unlikely to lead to any change. That was 1971 and it was not until the early 1990’s that the process to end apartheid began. After graduating at the end of 1991, my husband and I decided we would leave. We heard of a ship leaving for Australia and then onto South America and finally Europe. We made it to Australia but decided we were not made for life at sea and stayed in Sydney. Both my children were born there, and I also returned to university to do further study when my older daughter was only 3 years old. With a brief break when my second daughter was born, I studied for a further 7 years, graduating with a master’s degree in Audiology. I then worked continuously as an Audiologist in various capacities, for almost 40 years.

The end of my marriage would lead to yet another move. I met my second husband just prior to his return to New Zealand. After two years of commuting, we married, and I settled in Auckland. I was lucky to get a job coordinating the then fledgling cochlear implant programme, the device which changed the lives of so many profoundly deaf people. My career as an audiologist has been varied and has encompassed work in a centre for profoundly deaf pre-school children, establishing a successful private practice and latterly research at the university. Travelling to the impoverished island nation of Kiribati over a period of seven years, (pre Covid), our team of volunteers successfully oversaw the establishment of a desperately needed ear health programme, in a country where sanitation is difficult.

My daughters and me. L-R: Britt, me, Roanne

My husband Russ and me

I am now enjoying exploring other fields. I have always loved acting and in both NZ and Australia I performed in several amateur productions. I have now taken up ceramics and I really enjoy the challenge of creating with clay. I am also on the committee of the Zionist Federation and take an active interest in Israel Advocacy. I feel blessed that both my daughters also decided to settle here, and I now also have four grandchildren. The last couple of years have been challenging for all of us, but I look forward to the next chapter.

Footnotes:

1. Stein, Louis, The Exile of the Lithuanian Jews during the Fervor of the First World War (1914-1918). Translated by Judie Goldstein. Uploaded by Lance Onufer. Yizkor Book Project. Copyright © 1999-2011 by JewishGen, Inc. Updated 8 July 2006