From My Mother’s Kitchen

CLAIRE BRUELL speaks about the experience of being a child of Holocaust survivors who found refuge in New Zealand. Her memories are linked with the smells which came from her mother’s kitchen. It is a memory which also has led her to delve into the past in search of vestiges of a former way of life, peopled with ghosts, now vanished.

There is a chilling image which has stayed with me since the age of about 12. I am sitting in the kitchen of a friend whose mother is cooking me pancakes (palatschinken). For some reason I can no longer remember, we two are alone. She is from Eastern Europe, an excellent cook and plies me with fresh aromatic pancakes, one after another, oozing melted chocolate. At the same time she is telling me an unimaginable story of her experiences in Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp during the war. In particular she describes the details of Nazi atrocity and how her only child was taken from her, in front of her eyes. The juxtaposition of the terrible images from her story with the delicious richness and runny texture of the chocolate pancakes left an impression forever etched into my mind, as clearly as the sight of the number tattooed on her arm. I don’t know why she confided in me. I can only guess it was because, as she claimed to my mother, I reminded her of the lost child. Thus I gained an insight into the demons that must have plagued her and many others who shared similar experiences, for the rest of their lives. Instinctively I knew that her confidences were not something I should share with others.

As a Second Generation person, this memory and others like it have led me to delve into the past. I seek out family details and cook recipes from my mother, grandmother and mother-in-law to a point which others might consider obsessive. These links through food to a culture prevalent in far away times and places are important to me.

Palatschinken are tasty, filled with jam, honey, lemon and sugar or even a sweet cottage cheese mixture, but a melted chocolate filling is the ultimate. Here is my family’s recipe for palatschinken, the first thing I ever learnt to cook.

PALATSCHINKEN

Ingredients

250 grams flour

2 eggs

1/2 litre milk (approx)

Pinch salt

60 grams sugar (optional)

Mix all ingredients and beat to a runny batter.

In a pan, melt a little butter.

Pour in sufficient to cover the base of the pan thinly.

When pancake starts to brown, flip over and cook until slightly browned on both sides.

Turn out onto a plate and continue to cook pancakes until all the batter has been used.

My mother was Alice (known as Lizzie) Briess (nee Löwy). She was born in Luntenburg,(now Breclav) a small town near Brünn (Brno) in Czechoslovakia where her father was the local doctor. He had been the only child of 16 to have received education beyond school and had studied in Vienna. When Lizzie expressed a desire to attend University her father Isidor would agree to her studying only medicine. She studied at the Charles University in Prague in the 1930s but married my father Frank Briess just short of sitting the final exams for her degree. Considered a most desirable match, they married on 6th June 1937. They settled in Olmütz (Czech Olomouc) where Frank worked in the family grain business.

Lizzie Briess. Photo taken some time between 1937 and 1939 in Czechoslovakia. Barry the dog had to be left behind when Frank and Lizzie fled to London on 13 March 1939. The dog was left with a local farmer along with some of the family assets, which were buried somewhere in his garden. The same farmer was later involved in the plot to assassinate Heydrich, the Nazi ruler of Czechoslovakia. In later years the famer’s son continued to send cryptic messages to the Briess family informing them that the ‘flowers were still growing in the garden and it was not yet a good time to pick them’.

My parents fled the Germans and on 9th October 1939, arrived in Auckland. They went farming in what is now suburban West Auckland. During the years they were on the farm their refugee friends visited on weekends. No doubt the women tried out recipes on each other and discussed and compared the results and they probably talked of home and worry about family and the war. They lamented the unavailability of food and ingredients they were used to – gherkins, sauerkraut, sausages, herrings. At home in Czechoslovakia there had been a cook and servants. This was a different life! Lizzie and Frank wrote weekly to their parents in Czechoslovakia. Lizzie’s letters to her mother Marta were often about housekeeping and cooking. Fortunately they kept carbon copies of their typed letters, describing in detail their lives in New Zealand during the early war years.

Undated…(1940)

“The only news from the farm to report is that we bought a goose. We locked her up in the pigsty at night and during the day we let her walk around a fenced off paddock. You’re not allowed to fatten geese here. We fed the goose on maize and grass, looked after and protected her for 4 weeks and then we killed her. We were very proud that by correct feeding we were able to get rid of the fishy taste which the gooseflesh here usually has. Here, the geese wander freely over the farm and eat whatever takes their fancy, even fish. That’s why the gooseflesh tastes so bad. We had a proper Friday night dinner – young goose with sauce and barches (challah). Lovely!”

16/3/1940

“Franz goes to work and I begin cleaning up and cooking. Once a week I wash the bedclothes, as you wrote in my cookbook it should be done. Do you remember that? Washing is easier here in that we have a machine that looks like a mangle on a trough and we can wring out the washing. Summer and winter you can dry the washing outside. Once a week I bake bread with sour dough and yeast and once a week I iron….. Today’s lunch Naturschnitzl, cucumber salad, new potatoes and a butter cake….”

18/5/1940

“I don’t know if I described for you before the way our home is arranged. The place in which I spend most time is the kitchen…….On the farm we always have lots of supplies, especially me because every 5-6 days I bake a big loaf of bread…..The kitchen is very roomy. It’s painted olive green and beige. I cook daily, meat, fruit or vegetables, potatoes and dessert. Sometimes I bake a cake which lasts for 2 days, omelettes, kaiserschmarren, pancakes, apple dumplings etc. Besides I can make a wonderful butter pastry similar to Frau Fischkus’ recipe but with water and vinegar because rum is too dear. Although I won’t be as good a cook as you for a long time, I surprise myself at how well I get on and how good the results are. The guests always say so and I have a good reputation as a cook….We have a trolley, which is important here as I have no servants. I put everything in the kitchen on the trolley and wheel it in... On the buffet I have the candlesticks and the cups which you gave me for my birthday present.”

Claire’s mother brought her cookbook with her when she arrived in New Zealand and treasured it as a connection with her own mother, Marta.

This is a recipe for the caraway seed bread which Lizzie baked on the farm each week. It was then, and is still today, always popular. Nostalgia and the aroma of bread baking lead me to bake it now and then. Lizzie stopped baking bread each week when she and my father had to lose weight. The loaf can be varied in size and use of grains according to the type of bread you want. If you want a heavier bread, use more stoneground wholemeal flour or rye flour in whatever combination you like. For me what makes the bread special is the use of large amounts of caraway seed which give the bread its distinctive flavour.

CARAWAY BREAD

Ingredients:

2 tsp granular yeast

1 tsp sugar

Water

Caraway seed to taste (4 tblsp?)

Salt (to taste)

5 cups of mixed flours – white, stoneground wholemeal, rye.

(I use about 2-3 cups of white flour and the rest darker flour)

Leave yeast, sugar and water to “work” in a container until bubbling.

Place all dry ingredients in cake mixer together with bubbling yeast mixture and beat with a cup or so of the water.

Add water as required so that the resulting dough comes away easily from the sides of the mixer. It is a fairly heavy dough but should be elastic and still a bit sticky to touch. It can be baked without a mould “stand alone” or in a loaf tin. I usually keep adding water little by little until the dough forms a ball around the dough hook in the mixer. Purists are welcome to knead by hand. I have not noticed a difference in the finished product.

Butter or spray loaf tin, roasting tin or whatever container you want to cook the loaf in. Place loaf in pan and pat top down flat.

Wet top by sprinkling water roughly on top.

Sprinkle caraway seeds over the bread and pat down to make the seeds stick. This bread only requires one rising.

Bake about 10 minutes on a higher heat to brown the top (180 deg) and then turn down for about 30 minutes to 150 deg.

Bread is ready when a wooden skewer can be inserted in the middle and comes out clean of unbaked dough. Turn out immediately – don’t leave sitting in the tin or the bottom becomes soggy.

5/12/1940

“In 2-3 weeks I intend to bottle about 50 jars of plums. I’m borrowing the machine, the plums are growing on the farm. I’m paying the lady in plums, for the borrowing of the machine. Funny, isn’t it? I planted dill to use with gherkins, but this year unfortunately I can only make enough for us.”

27/6/1940 (letter to Frank’s sister Marianne and her husband Otto in America)

Today we checked on how our sauerkraut is getting on. I tell you it’s just great! First we’ll try a small amount, then we’ll sell it. We want to do the same with pickled gherkins. By the way, can you get them in America? I am also interested to hear if you can get Hungarian salami and how much it costs. My mouth waters! Can you get rollmops? You can’t get these things here. I suppose because it’s too warm.

3/2/1941

“I’m very proud of my first lot of salted gherkins. They turned out well. This week I’ll do 100 more and I’ll also do 2 dozen mustard gherkins. They keep longer. As well as these, I bottled 20 jars of plums. As you can see I’m taking good care of our stomachs. I enjoy it and I’m proud when things come out well. Of course, I’ve also got plum jam…..and three months later……The sweet and sour gherkins turned out quite well. The massergurken have already been eaten up and I still have about 11 jars of mustard gherkins. They keep well and we treat ourselves with them. I’m so pleased I’ll do some again,., hopefully soon. Slowly I’m making everything. I’m collecting recipes. Recently I made sweet and sour loin of beef. It says to us ” stale” meat which is hard to get. I make brine quite often. I like to cook as we did at home, mainly because I can do the dishes so well. I always think of you, what you would say about it, when something turns out particularly well. I also bake bread all the time”

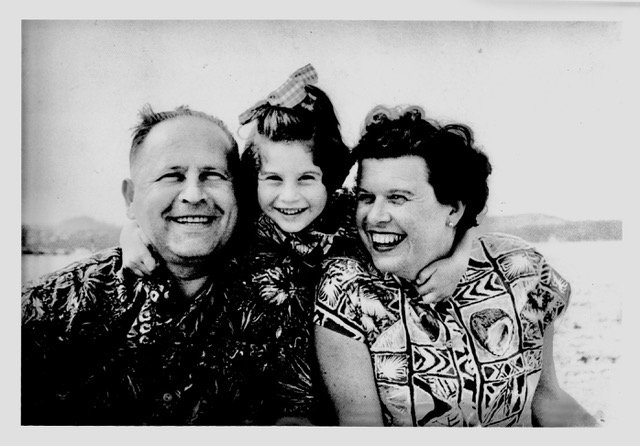

This photo of Alice and Claire was taken in the 1950s in their home in St Heliers, Auckland. In 1942, when Japan entered the war, the Alien Regulations changed to prevent Aliens owning property within a 15-mile radius of the airport. As the Briess’s farm was close to Whenuapai they were forced to sell and moved to Auckland. There they were manpowered into running a restaurant in Queen St known as the ‘Centre Way’ to cater for the American troops.

These letters were written during the war years, my parents’ early experiences in a new country. I had not yet been born so I was not part of their lives then. One of the things I do remember when I was growing up, is the coffee afternoons, a legacy from their former lives. Each Saturday morning my mother would bake several cakes and in the afternoon, their friends would arrive for coffee and to eat the fruits of her labours. Unless she hid the cakes, my father, who was cursed with the family liking for sweet food, would yield to temptation and when my mother came to serve the baking she would find a wedge missing from her topfentorte or kugelhupf.

GLEICHGEWICHT TORTE

The name is German and means “equal weight cake”. This is a cake which has local variations and was baked throughout Central and Eastern Europe. It is best made with fresh fruit. My mother-in-law used apricots or plums, my mother used cherries. My cousin, recently visiting from the UK told me she always bakes it at Rosh Hashonah, (Jewish New Year) which comes at the end of the northern summer. Tart fruit seems to be best suited for it. A wonderful New Zealand variation is to use tamarillos. Once again, this is a recipe which can be varied according to the number of people who are to share it.

Ingredients:

Eggs (4 for an average size cake or to fill a swiss roll tin)

Butter

White sugar

Flour

Weigh the eggs. Take note of total weight.

Separate the eggs and beat the whites.

Take the weight of the eggs and then the same weight of flour, butter and sugar.

Beat yolks, butter and sugar together.

Add beaten whites and sifted flour alternately until you have a cake dough. Turn into a swiss roll tin or equivalent.

Having de-stoned the fruit, set evenly and close together into the cake and bake on 150deg or so until the dough is cooked. If you have a lot of fruit this may take a while and sometimes I just turn off the oven and let it finish slowly.

Cut into slices. When cool, dust with icing sugar.

This cake is best the day it is made. It can be served with coffee or as a dessert. Cream, icecream or crème fraiche are seductive optional extras which few turn down.

12/7/1940

Today I tried your recipe for chocolate layer cake. I used butter instead of margarine as the margarine here is not like what we’re used to and butter is easier to get. It turned out very runny and after cooking it for half an hour it was only as firm as a cheese omelette. I think something went wrong. Please send me the recipe in more detail. Actually I am really grateful for all the recipes as I bake quite often and we like the variety. I would very much like the recipe for the cream that you fill kremschnitten with. I really have only a few recipes here.

6/6/1940

“A few days ago I got some chives. I know where I can get some horseradish and have a private source where I can get some dill. Besides this there is a Swiss here who makes wonderful sausages who supplies me once a week. His sausages are quite spicy. We eat quite a lot of cottage cheese which I make myself….So we have told you in every detail what makes us happy and the only thing missing is you. But this time will come soon, we are confident. Patience is the key. We are always with you in spirit and so I embrace you sincerely and remain….Your Lizzie.”

Marta Lowy (née Berger) maternal grandmother of Claire Bruell.

Despite Lizzie’s optimism, her dream was not to be realised. Marta shared the fate of over 120 other members of my close and extended family. She was deported from Brünn to Theresienstadt (Terezín) Concentration Camp in Bohemia, on Transport U.759 on 28th January 1942 and from Theresienstadt to Lublin (Maidanek) in Poland on Transport No.A1-196 on 23rd April 1942. Lizzie never heard from her again.

Only two first cousins, on Marta’s side of Lizzie’s family survived the war. On the farm Lizzie had suffered two miscarriages. Finally I was born in 1947. As a precious only child I was the focus of the undivided attention of both of my parents, but I believe I was particularly special to my mother. From time to time a rather irrational (to me) concern with my health and wellbeing surfaced, which I now realise is typical of the experiences of many others of the Second Generation. The horror and loss of the Holocaust were rarely discussed at home, although dead grandparents and an uncle were sometimes talked about. I was aware of the details perhaps by osmosis, however I instinctively knew that it was painful for my parents to recall that time. Besides, they did not want to dwell on the past. They wanted to get on with the present and the future, to “fit in”, and were always grateful to New Zealand for taking them in.

Claire Bruell in national Czech costume at the Annual Jewish picnic 1951.

So what does all of this mean to me, Claire, only child of Frank and Lizzie? For me personally, the death of so many of my family in the Holocaust meant that I grew up without siblings, grandparents or much of an extended family. There were few family stories for me to get to know my grandparents, great grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins. There is no “rogues’ gallery” of family photographs in our home. The photos have disappeared along with the people. This lack of a close family group led to feelings of isolation and “difference”. I ferret around as a genealogist, searching out information, vignettes of the past.

The interwar Czechoslovakia of my parents’ youth doesn’t exist any more. The Czech Republic I now visit is a different place, changed by years of communism, its once vibrant Jewish culture largely relegated to memorial status in Museums and Galleries. I don’t understand the language so it cannot be “my place”. What does remain is the connection provided by my parents’ letters and documents, the importance of food, traditions and values. My mother’s yearning to share her cooking successes and failures with her mother and for Marta’s approval, speaks volumes to me. And my parents did eventually establish a food business dealing in meat, spices, continental sausages and small goods, importing gherkins and other pickles and even producing them in New Zealand for a time.

Although when I was younger I longed only for the Anzac biscuits my school friends introduced me to, my mother’s earnest attempts with the recipes given to her by the mothers of my school friends never quite yielded the same results as theirs. They did not taste the same as those in the other lunch boxes at Kohimarama School. It is the nostalgia connected with the smells of Mum’s own baking, memories of frankfurters for weekend lunches, salami in my school sandwiches and the cottage cheese hanging in muslin over the kitchen sink that evoke my childhood. I pour over my mother’s handwritten cookbook, brown-stained, falling apart, with the translucent remains of a splodge of butter a memory on the page. I look at kugelhupf recipes, one from Tante Ilse, another from Tante Franci, yet another from Tante Paula and I can visualise them all sitting round over afternoon coffee, swapping recipes. These are my links with a past I never knew.

BIO

I was born in Auckland in 1947 and have always lived in Auckland. I studied for a Bachelor of Arts Degree at Auckland University majoring in History and languages. Three years of travel and living overseas were followed by completion of a Legal Executive’s Certificate from the Auckland Technical Institute (now AUT). Since 1980 I have been researching Family History and I write sometimes for Avotaynu, the International Review of Jewish Genealogy, as well as for other publications. I have been involved in the setting up of the Holocaust Oral History Project and in interviewing Holocaust survivors in Auckland. This has led to building up an archive of interviews with members of the Jewish community in Auckland. Pursuit of my interests in all areas of the arts and family business interests occupy my time. I have translated my parents’ letters 1939 to 1945 from German into English so that the picture of my parents’ early lives in New Zealand would not be lost in an English speaking country. Exploring my own family history is an enduring passion.

This project began as a forum for exchanging recipes, then slowly, took on a life of its own. For me personally my contribution represents a tribute to four matriarchs in my family: my grandmother Marta Löwy who was killed in the Holocaust at 54, my grandmother Adele Briess who survived Theresienstadt and my own mother, Lizzie Briess whose life was completely displaced by the Holocaust. My mother-in-law Lilly Bruell also came as a refugee to New Zealand and began a new life in 1939. These women have shaped my history.

This story first appeared in “Mixed Blessings: New Zealand Children of Holocaust Survivors Remember”, edited by Deborah Knowles, 2003 Tandem Press.