Charles Brasch

This biography, written by Sarah Quigley, was first published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography in 2000.

Charles Orwell Brasch was born in Dunedin on 27 July 1909 into an affluent commercial family. His father, Hyam Brasch, was a lawyer of Jewish origin; sensitive to prejudice, he later changed his name to Henry Brash. Charles’s German-born mother, Helene Mary Fels, was related to the Hallensteins, a family which established itself as goldfields merchants in Otago in the 1860s and later began a nationwide chain of clothing stores. In 1911 Helene gave birth to Charles’s sister, Lesley Mary; pregnant for a third time in 1914, she died suddenly of a haemorrhage. Brasch later described this event as ending his ‘childhood proper’ at the age of four.

Brought up in Dunedin by his father, his aunts, and a succession of housekeepers, Brasch spent much time at Manono, the large red-brick home of his maternal grandfather, Willi Fels. A businessman, Fels was also a keen traveller and art collector, and it was under his influence that Charles developed a lifelong interest in European culture. Later, despite strong opposition from Hyam, Fels supported his grandson’s decision to pursue a career in the arts. He was the ‘rock and centre’ of Brasch’s life from childhood to middle age.

At the beginning of 1923 Brasch was sent to board at Waitaki Boys’ High School, Ōamaru. During his three years there he began writing poetry, which was published in the school magazine, the Waitakian; he was encouraged in this by the school’s eminent headmaster, Frank Milner. At Waitaki, too, he formed a lifelong friendship with James Bertram, who later became a respected writer, critic, and academic. It was with Bertram and Frank Milner’s son, Ian, in 1932 that Brasch first discussed the possibility of publishing a substantial journal of the arts to succeed the short-lived Phoenix.

After three years at Waitaki, and half a year with Fels ‘preparing’ for his European experience, Brasch entered St John’s College, Oxford, in October 1927. His three years at St John’s were marred by the pressure of his father’s expectations, which directly opposed his own: instead of excelling in law and rowing, he took an ‘ignominious Third’ in modern history and began seriously pursuing a writing career. Among his contemporaries at Oxford were W. H. Auden, Cecil Day-Lewis, Stephen Spender and Louis MacNeice, and Brasch followed their example by publishing poetry in prominent student magazines. He also travelled in Italy with his relatives, the de Beers; his cousin Esmond de Beerhelped to form his standards in the appreciation of literature and art.

A friendship with fellow student Colin Roberts led him into an area of interest which both engrossed and side-tracked him for three years: archaeology. In 1932 he participated in an expedition to Egypt under the leadership of John Pendlebury; he returned to Tell el Amarna, in the Nile Valley, for a further two seasons. Between digs he lived in London’s Primrose Hill and studied Arabic and Egyptian history at the University of London’s School of Oriental Studies; some months were spent in further travel throughout Europe. Eventually, he became disillusioned with the idea of a career in archaeology, but his first two volumes of poetry and several unpublished short stories reveal the lasting influence of Egypt on his writing.

Brasch returned to Dunedin and worked in the family business for most of 1931, but felt that his future lay in England. The poetry he wrote during the 1930s, which he described as his first ‘real’ poetry, is marked by his divided loyalties to two countries; written in England, it was published in New Zealand journals such as Phoenix and Tomorrow. His exploration of the paradoxes of European settlement in New Zealand was a theme shared by other writers of his generation, such as A. R. D. Fairburn and R. A. K. Mason. The uneasy, elegiac tone of his first two volumes became a hallmark of his poetry.

Fortunate enough to be living on private family means, Brasch was free to travel widely; he spent time in Italy (whose culture he adopted as an artistic ideal), France, Germany, Greece, Palestine, Russia and the United States. Yet the problem of identity which was central in his poetry plagued him in daily life. In 1937 he took a teaching position at a school for ‘problem’ children, which, for the first time in his eyes, justified his existence. The Abbey school, based on the radical Summerhill School in Suffolk, was situated at Little Missenden in the Chiltern Hills, and he taught English and history there for most of 1937–39, visiting New Zealand again in 1938.

In Hawaii with his father when war broke out in 1939, Brasch felt it his duty to return to England. He remained there (in and around London) for the next six years. Exempted from army service because of slight emphysema, he spent some months firewatching and then undertook intelligence work for the Foreign Office until the end of the war. Arriving back in Dunedin in 1946, he at last found his métier when, the following year, he founded Landfall, which he was to edit for 20 years.

In this position Brasch had a significant effect on the way the arts developed in New Zealand. A meticulous and at times exacting editor, he made Landfall not only a literary journal but also a forum for critical comment on life and culture in New Zealand. He insisted that the arts in New Zealand ‘must … depend on the European tradition’, and he judged them against the highest standards of that tradition. His exclusion of work that did not meet his exacting criteria for craftsmanship led some to judge Landfall as élitist, yet his aim was always to establish a worthy indigenous culture. It was in New Zealand rather than England, moreover, that he gained a reputation as a poet. Apart from a few poems in periodicals and magazines, his only published work in England was a brief foray into drama. His first two volumes, The land and the people (1939) and Disputed ground (1948), were published at the Caxton Press in Christchurch, under the direction of Denis Glover.

The poetry of Brasch’s third volume, The estate (1957), reveals a preoccupation with the rediscovery of his home country. The same quest for identity, both global and personal, remained at the heart of his fourth collection, Ambulando (1964), although by now his style was becoming more compressed and less lyrical. His contribution – as editor, poet and patron – to New Zealand culture was recognised in May 1963 by the award of an honorary doctorate from the University of Otago.

On giving up the editorship of Landfall in 1966, Brasch found time for a variety of occupations, including the study of Russian, the joint translation of Punjabi poet Amrita Pritam’s work (necessitating several trips to India), and a brief foray into publishing with Janet Paul as the Square and Circle Press. He served on a number of organisations, including the Dunedin Public Library Association, the management committee of the Otago Museum, the Hocken Library Committee, and the visual advisory committee of the Arts Advisory Council, and he gained a reputation as a patron of New Zealand culture. He had lectured part time in the English Department at the University of Otago in 1951, and to the end of his life he continued to give guest lectures at universities and institutions throughout New Zealand.

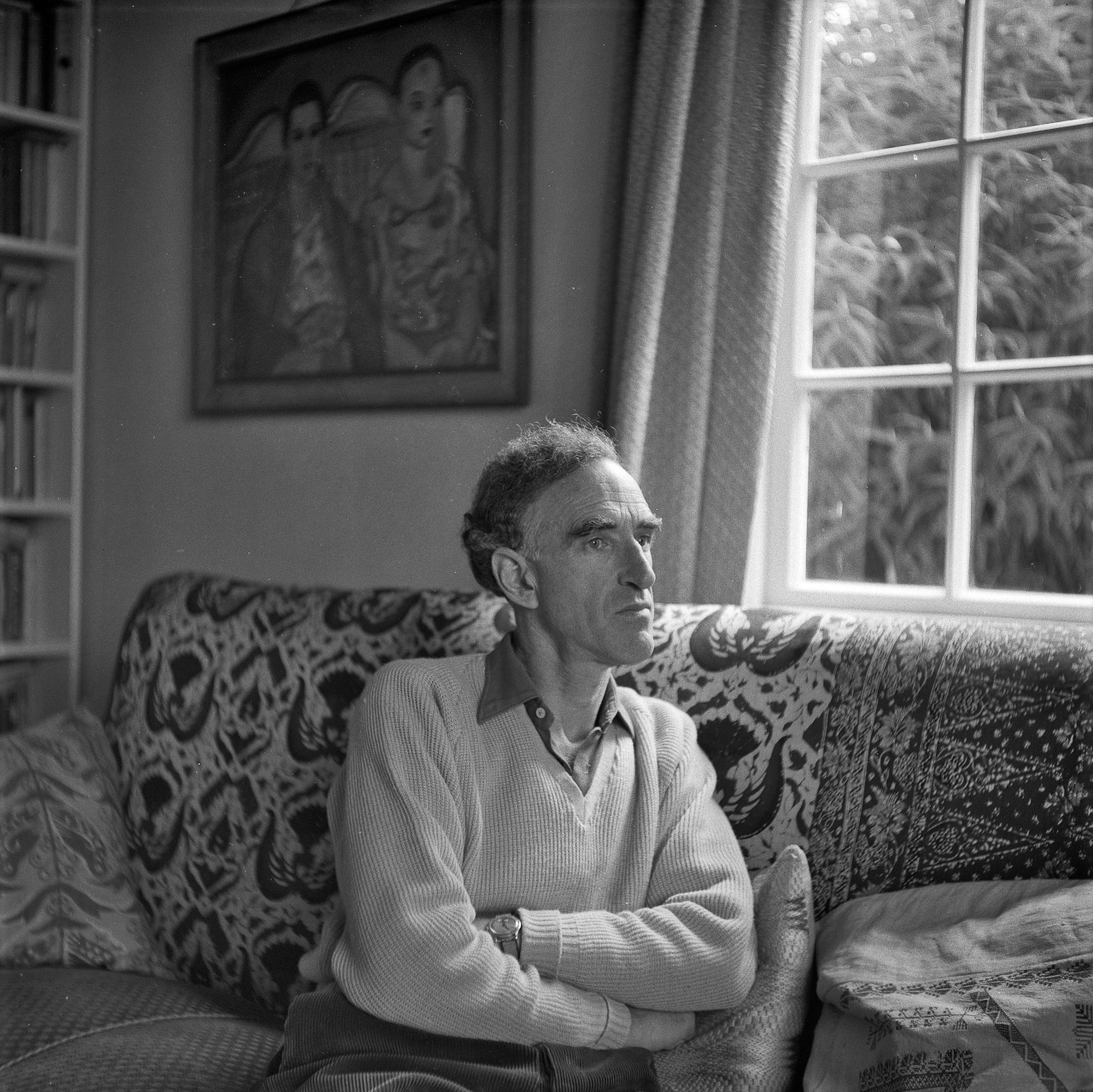

Despite his high public profile, Brasch remained a man of deep reserve, both personally and poetically, which was reflected in his intense, somewhat austere appearance. The establishment of the Robert Burns Fellowship at the University of Otago was widely attributed to him; other financial aid to artists and writers, many of whom were personal friends, was also usually anonymous. Brasch had a wide circle of friends, and for a time lived with the Dunedin artist and drama producer Rodney Kennedy, but otherwise made no exclusive emotional commitments.

His poetry continued to reflect the difficulty he had in defining, while still protecting, his inner self, and this became the focus of his substantial fifth collection, Not far off (1969). His final volume, Home ground (published posthumously in 1974), is still more personal, speaking in a newly modernist voice of coming to terms with old age and illness. During his final years he continued work on his memoirs, which were published posthumously as Indirections in 1980; the typescript covered the years from his birth to 1947.

A two-month trip to Europe in April 1972 included an appearance at the Poetry International festival in Rotterdam. When Brasch returned to New Zealand he became ill with cancer. In March 1973, suffering from Hodgkin’s disease, he entered Wakari Hospital under the care of his close friend Dr Deirdre Airey; he returned home in May to be looked after by Ruth Dallas and Margaret Scott. Throughout his final months he continued to write fragments of poetry. He died on 20 May 1973, at his cottage at 36A Heriot Row, leaving a rich legacy of books, paintings, and personal papers to Dunedin’s Hocken Library. A further collection of books was left to the University of Otago library, which established its Charles Brasch Room in his memory.

Sarah Quigley. 'Brasch, Charles Orwell', Dictionary of New Zealand Biography, first published in 2000. Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/5b40/brasch-charles-orwell.

Image header above: Portrait of Charles Brasch at his home in Heriot Row, Dunedin, 1960. Reproduced with the permission of the Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hakena, University of Otago. Photographer unknown.