Karl Wolfskehl

by Friedrich Voit

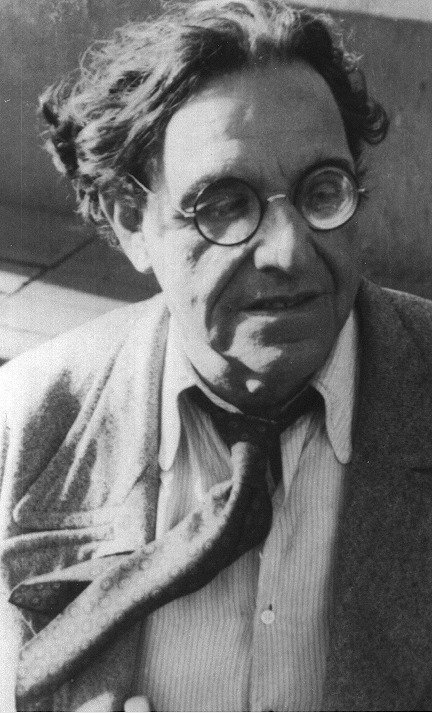

Image: 1939 by Maja Blumenfeld, courtesy F. Voit

‘Only from the farthest comes forth the renewal’ [1]

A sketch of Karl Wolfskehl’s life and work.

by Friedrich Voit [2]

When Karl Wolfskehl arrived in Auckland on July 3, 1938, he was virtually unknown there. A few short newspaper articles in Australia and New Zealand had introduced him as a ‘poet and philosopher, an exile from Germany’,[3] and these helped to establish first contacts. There was nobody who had more than the scantest knowledge of his personality or his work. Wolfskehl was, of course, aware of this, and it was part of his decision to travel to this country furthest away from Europe. The 68-year-old writer had come to New Zealand to find ‘inner peace’ and ‘distance from fear and confusion’ which had increasingly burdened his mind since anti-Jewish persecution had driven him out of his homeland in 1933 and into exile to Italy. In the twilight of his life Wolfskehl longed for a safe place, a ‘poet’s refuge’ [4], far away from the political turmoil of Europe, where he could continue his life dedicated to the achievements of the human mind in culture and the arts. He even hoped to find inspiration again for new poetry.

Karl Wolfskehl was born into a wealthy assimilated Jewish family on September 17, 1869, in Darmstadt––two years before the unification of the German Empire. Darmstadt, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Hesse-Darmstadt, was then a small town of around 30,000 inhabitants. The family, which––as the poet later claimed in his poem An die Deutschen (To the Germans)––had its roots in the region already for more than a thousand years, had close ties to the court, and was part of the local social elite. Wolfskehl’s great-grandfather Heyum had founded a banking business around 1800 in which he served as banker to the Duke. His father, Otto Wolfskehl (1841-1907) married, in 1868, the banker’s daughter Paula Simon with whom he had three children: Karl, Margarethe (1871-1904) and Eduard (1874-1943). Two years after her premature death in 1878, Otto married his non-Jewish second wife, Lilli Schulz, a renowned concert pianist, who became a beloved stepmother to his young children. In 1881, Otto Wolfskehl sold the family bank in favour of a distinguished career in regional politics and his other social interests.

Karl Wolfskehl, as he later recalled, grew up with a sense of a ‘seemingly unshakable social security’[5] provided by a privileged family environment. After some private schooling he entered the ducal Gymnasium which equipped the boy with a humanistic education focusing on classical languages (Greek and Latin), history and German literature. The young student could also develop his intellectual interests in his father’s library which held a rich collection in the fields of history of religion and philosophy. Music played a major role in his upbringing through his stepmother and his father who was an accomplished violinist. The family maintained strong links to the Jewish community, where Otto Wolfskehl was a member of the communal board. But Jewish customs and practices were only adhered to loosely, as was common in many assimilated Jewish families where Christmas had replaced Hanukah.

In his essay Ibsen-Jugend (Ibsen Youth)[6] from 1928 Wolfskehl looks back on his time as a high school and university student. The rising national pride after the founding of the German Empire in 1871 had given this generation a new sense of importance. For many of them, less interested in the rapid developments in technology and science, or social change, it was high culture and the arts which mattered. Ibsen’s plays especially appealed to the academic youth for they challenged moral norms and demanded a striving for truth and self-awareness. Soon they would discover Nietzsche. Wolfskehl read modern literature extensively both in the original and in translation as well as classical literature and German mythology. Between 1887 and 1893 Wolfskehl studied at the ducal university in Giessen and spent a few semesters at the universities in Leipzig and Berlin. He studied widely with the main focus on German literature, history and history of Religion gaining a doctorate with a thesis on German mythology. In the biographical note at the end of his thesis, Wolfskehl states with obvious self-confidence ‘Ich bin Jude’ (I am Jewish). At this point of his life and career this was a remarkable emphasis of his spiritual roots, considering the Germanic topic and the existing anti-Semitism, particularly in conservative academic circles.

Like many youths at this time with his background and interests, Karl Wolfskehl wrote poetry from early on, but he dismissed almost all of it[7], when in 1892 he encountered Stefan George’s poetry and a few months later met the poet himself. It was a life-changing moment for the 23-year-old. As he decades later declared: ‘My fate was sealed, my life had a meaning’.[8] George, only a year older than Wolfskehl, was still little-known outside a small circle of friends and literati, but with his early self-published poetry he established an important bridge with the European Symbolist movement at the end of the 19th century. Traveling extensively in Europe, he had met Stéphane Mallarmé in Paris, and other poets in Holland and Belgium. In Vienna he also befriended the 17-year-old Hugo von Hofmannsthal who had just published his first poems.

Wolfskehl recognized at once the superior talent of Stefan George. Captivated, ‘only and alone by the magic power of George’s poems, of the formed words’,[9] he was convinced, that this poetry heralded a new beginning in German art and literature. He perceived George as the founder of a movement hailing poetry and the arts as the foremost human achievement. Wolfskehl was by no means the only one to recognize the impact of George’s poetry, but none of the other early admirers went as far as him in his devotion. Soon Wolfskehl referred to George as the Master and saw himself as a disciple in the service of the revered poet. Stefan George, deliberately avoiding wider publicity and cultivating an aristocratic and elitist seclusion, differed in his personality greatly from his close collaborator and friend Wolfskehl who had many specialized interests, collected books, walking sticks and elephants, and maintained a multitude of contacts in the world of the arts and learning. However, the never wavering subordination to George and his ideals, already puzzling some of the contemporaries, gave Wolfskehl a focus and centre which held together his diverging quests and provided him with a norm and guidance in difficult times later in his life. George’s aesthetic and artistic ethos formed the inspirational base of Wolfskehl’s own oeuvre.

After completion of his university studies, Wolfskehl resisted his father’s wish to enter an academic career. He had–– in the steps of Stefan George––found his vocation: a life devoted to higher aspirations in literature and the arts as a poet and private scholar. He began to publish poetry, short aphoristic prose, and essays, like the programmatic Der Priester vom Geiste (The Priest of the Spirit), mostly in George’s journal Blätter für die Kunst to which he became one of the main contributors. His poetry, praised by George for its own tone and stylishness, was also published in two small volumes, Ulais in1897 (the title an eponym for his friend Louisa) and Gesammelte Dichtungen (Collected Poetry) in 1903. Together with George, he compiled the influential three-volume anthology Deutsche Dichtung (German Poetry; 1900-1902). Wolfskehl then wrote a few poetic dramas Maskenzug 1904, Saul (1905) Orpheus, and Sanctus (1909) which inaugurated an exclusive dramatic form befitting George’s elevated aesthetics and ethos. These plays were not performed for the general public, but as private and celebratory events amongst and with friends.

In December 1898 Wolfskehl married Hanna de Haan (1878-1946), the daughter of the Dutch-born Darmstadt court concertmaster Willem de Haan (1849-1930). The couple set up residence in Munich, the cultural centre of Southern Germany, which Wolfskehl already knew well from earlier stays. With the birth of two daughters, Renate (1899-1976) and Judith (1902-1983), the family had to move into a larger home in Schwabing, which soon came to be one of the pre-eminent meeting places for local and visiting literary and artistic personalities.[10] The Wolfskehls’ monthly jour fixe and their parties during the carnival period were legendary. Hanna shared her husband’s devotion to Stefan George, who over many years regularly stayed with the family for several weeks at a time, usually early in the year. At their last apartment house in Munich, Wolfskehl even rented an additional small flat with the legendary ‘Kugelzimmer’, named after the ball-like lamp, where George could sojourn whenever he came to the city.

Wolfskehl’s restless activities and engagements governed the unconventional life of the family. He was often away on shorter or longer trips alone or with friends within Germany or abroad. Frequently he travelled to Italy or Paris, or holidayed with his family in Holland. With the illustrator Alfred Kubin (1877-1959) he undertook a month-long trip to the Balkans in 1909, and a year later a voyage to India with his painter-friend Melchior Lechter (1865-1937), from where, however, he had to return prematurely because of illness. The names of some of the numerous and still-known friends and acquaintances amongst the writers, artists and scholars living in Munich, with whom Wolfskehl had intensive contacts during the years before World War I, may indicate the central role he played in the Munich cultural life of that time, and gave him the nickname ‘Zeus of Schwabing’. There was the somewhat mysterious ‘Cosmic Circle’ around Alfred Schuler (1865-1923), with the philosopher Ludwig Klages, (1872-1956) which fell apart in 1903/4 because of Klages’ anti-Jewish sentiments. Wolfskehl met with Thomas Mann and Hugo von Hofmannsthal; he befriended Rainer Maria Rilke and Ricarda Huch. For Alexander von Bernus’ (1880-1965) ‘Munich Shadow Puppet Theatre’ Wolfskehl wrote three plays: Wolfdietrich und die rauhe Else (1907), Thors Hammer (1908) based on German mythology, and the oriental scene Die Ruhe des Kalifen (The Calif’s Rest, 1908). His famous library of first and rare editions, built up over decades, gained him a reputation as one of the notable bibliophiles of his generation. In contrast to George, Wolfskehl had a keen interest in modern art both as a collector and as a friend of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, Gabriele Münter, Paul Klee and Franz Marc. He also involved himself with the emerging cultural Zionism and Jewish thought in his friendships and correspondences with Martin Buber11 and the orientalist Abraham S. Yahuda (1877-1951).

As for Europe, World War I and its consequences marked a major change in Wolfkehl’s life. Initially he like many of the leading intellectuals enthusiastically supported the German military actions, but in the course of the war this was replaced by a disillusioning realisation of the extent and futility of the destruction it brought. The lofty ideals of renewal and transformation of Germany through the arts and literature had evaporated in the face of reality. As a consequence of the war and the ensuing inflation Wolfskehl lost most of his inherited wealth and his financial independence. The family had to leave their comfortable home in Munich and moved to a country estate at Kiechlinsbergen, near Freiburg, which Wolfskehl had bought in 1915. This move also brought a loosening of his friendship with Stefan George, who had to give up the ‘Kugelzimmer’ and had already begun to turn to younger ones amongst his followers. The fifty-year-old Wolfskehl was deeply unsettled by these changes. Forced now to earn a living he even contemplated a radical new beginning as a teacher in a distant place like Sumatra[12], but then took up a position as private tutor in Italy, where he stayed for over three years. Friends and contacts in Munich made it possible for him to return in 1925 to the city, where he rented a modest flat, only seeing his family during holidays in Kiechlinsbergen.

Very quickly Wolfskehl established himself as an editor for Rupprecht Press, publishing numerous literary texts as a translator from several languages, e.g: the medieval Latin poetry of the Archpoet (1921), de Coster’s Ulenspiegel (1926) from the French, and Bertrand Russell’s Sceptical Essays (1930). But he was soon best known as a cultural journalist writing for local and leading national newspapers and periodicals. When he joined the Rotary Club in 1927 Wolfskehl took on the editorship of the club’s national journal Der Rotarier. In many letters at the time he complained that his diverse work and commitments exhausted him and left him no time for any serious poetry. He wrote only a few dozen occasional poems mostly of a lighter and witty kind. Two poetry publications––a second edition of the Gesammelte Dichtungen (1921) and Der Umkreis. Gedichte und dramatische Dichtungen (The Sphere. Poems and Drama Scenes, 1927) which collected poetry to 1919, published before in the Blätter für die Kunst––didn’t find a new or wider audience. Critics judged these poems as dated, too close in their exalted tone and forms to those of Stefan George. Only one or two were able to recognize Wolfskehl’s distinctive characteristics, like the musicality of his verses or the mythological and apocalyptic visions. His considerable name as a writer rested in the 1920s much more on his essays, of which he published a selection in Bild und Gesetz (Image and Law, 1930)[13]. This widely reviewed and acclaimed volume appeared in the year after his 60th birthday when he was congratulated nationwide in numerous articles and praised by Walter Benjamin as a man of manifold ‘Witterungen und Regungen’[14], i.e. for the wide-ranging intellect, knowledge and insight exhibited in his essays.

Wolfskehl was an acute observer of the political changes in Germany and early sensed the looming threat of the rising Nazi-movement for the country and himself as a Jew. When he suffered a severe gastrointestinal illness in 1931, he stayed for many months in Italy and Switzerland to recuperate and to wait out developments in Germany with its ‘poisoned atmosphere’, only returning for brief stays. To friends he described himself already as an émigré. At the turn of 1932/3 he lived again for a few weeks in Munich, before fleeing from Germany on the morning after the burning of the Reichstag on February 27, not suspecting that he would never step on German soil again. His fears were quickly confirmed when his contract with the newspaper publisher in Munich was abruptly cancelled and the Rotary Club excluded him from its ranks, together with all other Jewish members. Wolfskehl now was an exile.

In 1933, Wolfskehl stayed with friends in Basel and Zürich, and lodged for some time in the small village of Orselina near Locarno, before he moved at the end of the year to Rome. To his own surprise, Wolfskehl responded to the trauma of banishment from Germany––the second radical turn in his life caused by external forces––with renewed creativity: involuntarily freed from the necessity of journalistic work, he began writing poetry again. In quick succession he wrote the sequence Die Stimme spricht (The Voice Speaks) of which the first poems were published later in the year in Jewish journals. Expelled from Germany, Wolfskehl evoked in this cycle his Jewish roots. Beginning with a dialogue between the divine Voice and the poet he evolves more and more into a voice for the Jewish people. The poems celebrate Jewish history, the strength of survival in the face of centuries of adversity, and God’s protective covenant with the Jewish people after the exodus from Egypt. Since German publishers were no longer allowed to publish books by Jews, the small black volume appeared in the ‘Schocken Bücherei’ of Salman Schocken in autumn 1934. It became Wolfskehl’s most widely read collection, which reached, consoled and encouraged German Jews, who had, like its author, to come to terms with the sudden persecution and exclusion in their homeland.

Parallel to the poems of Die Stimme spricht, Wolfskehl composed the first versions of his great poem An die Deutschen (To the Germans). This poem conjures up in seven stanzas his personal relationship with his homeland (where his ancestors had been living for more than a thousand years), and his own involvement with and contribution to German culture and literature, culminating in his friendship with and dedication to Stefan George. He distributed copies of the poem amongst his friends and some of them were deeply disturbed when Wolfskehl added a second part, Der Abgesang (The Coda) in which the poet announced his renunciation of his German past––in answer to the Burning of the Books in May 1933 and the Nuremberg Laws of 1935 which divested German Jews of their citizenship.

Die Stimme spricht and An die Deutschen together are a powerful poetic renunciation of what Wolfskehl had believed in all his life: the symbiosis of Jews and Germans in the German cultural region. This symbiosis was always fragile and interspersed with persecutions, but with the emancipation of Jews in the 19th century it appeared that it could be achieved, paving the way for equal participation as reflected in the illustrious list of Jews and their accomplishments in the arts, music, literature and science. But again, it turned out to be an illusion––this time catastrophic.

During the first years of the European exile, Wolfskehl met up with friends who had also left Germany or were living abroad. He renewed his friendship with the philosopher Margarete Susman and his acquaintance with Thomas Mann, who in 1933 had not returned from a trip to France and lived near Zurich. When Mann read An die Deutschen he offered to publish the poem in his exile journal Maß und Wert (Measure and Value), but Wolfskehl declined out of fear for his family in Germany. A highlight of this time was a reunion with two of his oldest friends, Melchior Lechter and the Dutch poet Albert Verwey in Meilen at Lake Zurich in September 1935.

Because of his very limited eyesight, Wolfskehl relied on secretarial assistance. His friend Edgar Salin had brought him into contact with a young woman from Berlin, Margot Ruben, who had just completed her PhD in economics, but––as a Jew––had no prospect of any career in Germany. She immediately accepted Wolfskehl’s offer to work for and with him for a very modest remuneration as his assistant. Familiar with the Georgean ideals and ethos, she felt deeply honoured to join Wolfskehl in his exile. They met in Florence where Wolfskehl was living at that time. Within a short time the working relationship changed, the twenty seven-year-old assistant and the sixty five-year-old poet were lovers, and Margot became the partner and faithful helper of Wolfskehl in his remaining years.

When life in Florence, which in these years was the home of many exiles from Germany, grew too busy, Wolfskehl decided to move to the small fishing of town of Camogli, near Genoa,[15] and a few months later rented an old villa in the nearby village Recco, where he stayed for his remaining time in Italy. Because of the closeness of the railway station in Genoa it was a convenient location to start out for travels, especially to Switzerland, and to receive visitors.

After composing the sequence Die Stimme spricht and the An die Deutschen, Wolfskehl’s poetic output slowed down somewhat. He took up the cycle INRI again, begun in 1933 and originally entitled Triptychon Christianum, a recondite contemplation of the Messianic figure of Christ from a Jewish perspective. But his main project was the translation of mediaeval Hebrew lyrics which he undertook in co-operation with Salman Schocken’s Research Institute for Hebrew Poetry in Jerusalem. The institute provided Wolfskehl with literal translations and commentaries to the form and content of the poems, which Wolfskehl was to transform into poetic German adaptations as he had done in his popular edition of Älteste deutsche Dichtungen (1909). The distance between Palestine and Italy, however, hampered the work, and Wolfskehl completed only a small selection[16], which once more documents his extraordinary linguistic and poetic gifts for such adaptations.

The years in Italy passed quietly with literary work, receiving and undertaking visits, until autumn 1937, when Mussolini and Hitler began to join forces and antisemitism entered politics in Italy too. Wolfskehl sensed, that with German militarisation and fascist regimes in Italy and Spain, a new war in Europe was looming, and he decided to set out again––this time away from Europe. This became possible when he sold his valuable library to his publisher Salman Schocken, who already possessed a well-known collection of German and Hebrew books. With the proceeds, he secured the support of his wife and daughters in Germany and a small annuity from Schocken to provide for himself wherever he might go. Wolfskehl had contemplated several options. For a while Mexico was one, but in the end he choose to go as far away as possible from Europe, to the Antipodes, to New Zealand. There he hoped to find asylum for himself and his work and the spirit and liberty Europe was about to betray and to lose––as he expressed in the short poem encouraging Margot Ruben to join him in his new start in the unknown:

There still flourishes a land in God and free

From the desert-devil of the brown ape-time,

Last beyond the sea, southward, most secretly: a north––

There small shoots thrive again. Believe! Let’s go aboard.

Wolfskehl and Margot Ruben left Europe in May 1938. The sea- voyage took them via Colombo to Australia where they stayed for a few days before traveling on to New Zealand, landing in Auckland on July 3. Upon arrival, Wolfskehl gave an interview to the New Zealand Herald in which the exile from Europe expressed the high hopes he held for his stay: ‘I am coming to a new country, an entire new world, a new mentality and outlook, and I am enormously interested at the prospect. […] From the glimpse I had of Australia, it seemed to me that the life there was not of to-day nor yesterday, but of tomorrow […] It is a life without the burden of the past. Its history is a promise of future life, and, from what I have read of New Zealand, I think it will be the same here.’[17]

Wolfskehl–already aware that it would be impossible to obtain a refugee visa for any country at his age–had left Italy with a return ticket and arrived in New Zealand on a tourist visa which allowed him to remain in the country for six months. Any future plans weren’t finalised at this stage. Soon, however, the reality of the time caught up with him, when he learnt that with the new anti-Jewish legislation in Italy[18], a return there was prohibited and his ticket would be invalid. He was forced to apply for refugee status. A submission for a visa in Australia was declined, despite recommendations from the likes of Thomas Mann. However, the help of refugee supporters like the lawyer Louis Phillips, Arthur Sewell, the professor for English at Auckland University, and Douglas Robb, the reformer of the New Zealand health system, the latter two acting as guarantors, secured Wolfskehl and Margot Ruben a residency permit in January 1939. Symbolically chosen as the ‘globe’s last island reef’’ New Zealand was to become the ‘Dichterasyl’[19] (poet’s refuge), Wolfskehl had been looking for.

Already during the voyage Wolfskehl had felt again the urge to write poems. Taking comfort in his renewed creativity he wrote a handful of poems in which he reflected his radically changed situation. Choosing the figure of the ‘eternal’ Job, the ‘withstanding sufferer’[20] of the Bible, Wolfskehl mirrors his own thoughts, anxieties and feelings caused by the new and unfamiliar environment. Job appears as a modern exile: punished for the misdeeds of his forbears and his own generation he reaches a place where he can survive by withdrawing into himself–‘walled by yourself’ as it says in the poem ‘Outward Bound’. With these and other autobiographical poems Wolfskehl establishes the image of the lonely exile far away from his past and friends, an image which he continued to evoke in poems and in many letters he would write in New Zealand, but which belied somewhat his social life and the new friends he found there too. The wish to immerse himself in the new cultural environment and to improve his English led Wolfskehl to translate English poetry: a poem by the Australian Christopher Brennan (1870-1932) ‘We sat entwined an hour or two together’[21] whose poetry he had discovered in during his stay in Sydney, and a selection of Lord Byron’s Hebrew Melodies[22].

In 1938 Auckland was by far the largest city in New Zealand, but with about 250,000 citizens it was less than half the size of Munich, and the houses with corrugated iron roofs on quarter acre sections were very different from those in European cities. After a short stay in a motel Wolfskehl and Margot Ruben found a two bedroom flat in Esplanade Road, Mt. Eden, where they stayed for about three and a half years. It didn’t take long for them to make acquaintances. They met with Rabbi Alexander Astor and the local Zionist leaders Very Ziman and Louis Phillip, and they befriended refugee families like the Blumenfelds, in whose house Wolfskehl celebrated his 70th birthday in 1939, and the Steinhofs. The circle which formed around them soon included New Zealanders like the teacher Phoebe Meikle23 and her friend Millicent Hoyle and the English immigrant Pia Richards, daughter of the English novelist Maurice Hewlett, who was to become for many years a regular visitor to read and discuss English literature with Wolfskehl. Despite his constant complaint about the loneliness of his exile, expressed in numerous letters to his friends all around the globe, Wolfskehl was never really alone in Auckland. There were always people, often much younger than he, who came and visited him. Especially when Margot Ruben embarked on her own career, lecturing and teaching.

When World War II started in September 1939, all refugees from Europe were required to register and were then classified as ‘enemy aliens’, a term resented especially by Jewish refugees for its ambivalent connotation. Wolfskehl and Margot Ruben––like most Jewish refugees––were categorised as Class D, which implied some restriction, such as not being allowed to own a radio or camera, or to travel within New Zealand without police permission. All mail was censored and written with that in mind.[24] Otherwise daily life remained largely unaffected. The impulse to write poems continued and Wolfskehl was able to compose the forth ‘tablet’ which completed the cycle INRI and he began the cycle Mittelmeer (Mediterranean). This sequence of poems was inspired by a fig-tree Wolfskehl found in the garden of their flat which he addressed as a fellow exile displaced in a faraway country. In these poems, Wolfskehl contemplates the Mediterranean and its long history as the cultural cradle of European culture and the threat of its demise in the present.

With deep concern, Wolfskehl followed the news about the initial German military successes in Europe and the Middle East, and, horrified, learned of the deportation and murder of the European Jews and the temporary threat to Palestine where so many Jews had fled.

A trip to the South Island in January 1941 was an uplifting break, despite being the only major journey Wolfskehl was able to undertake in New Zealand. It was planned as a visit to friends, but also led to new inspiring acquaintances and friendships. In Dunedin he stayed with the Steinhofs, where Caesar had found a position as religious teacher for the Jewish community. They introduced him to two refugee scholars, the philosopher Felix Grayeff and the medical researcher Dr Walter Griesbach, whose medical advice the poet appreciated in the ironic self-portrait ‘Medico Magistrali’, as well as to other academics at the university. From there he travelled on to Christchurch to sojourn with the literary scholar Paul Binswanger and his artistically gifted wife Otti,[25] old friends from Germany, and the Christeller and Munz[26] families, whom he had met in Auckland and Florence. A planned meeting with Karl Popper who had been living in Christchurch since 1937 didn’t eventuate. The Binswangers, who were involved in the lively art and literary scene in Christchurch, brought the book-lover Wolfskehl into contact with the people and writers around the Caxton Press, then the leading publisher of modern New Zealand poetry and literature. Wolfskehl appreciated their initiative to create an authentic New Zealand literature; he praised Allen Curnow’s poems, and befriended Denis Glover and Leo Bensemann whom he admired as printer and illustrator.[27] It was a mutually inspiring encounter between the lettered European poet and the younger New Zealand artists. In Wellington, on his way back to Auckland, he met with the architect and composer Richard Fuchs (1887-1947) who had won a major prize in Germany for setting poems by Wolfskehl to music in his composition Vom jüdischen Schicksal (About the Jewish Fate; 1937)28, and who had like Wolfskehl found refuge in New Zealand in 1939.

A few months after his return Wolfskehl suffered a severe heart attack. It was the first major setback in his health and he recovered slowly, helped by the growing circle of people around him, mostly much younger, who visited and cared for him. There was the young literature student from Vienna, Paul Hoffmann (1917-1999), who read to and studied with him, while completing his degree at Auckland University, and his friend Georg Tintner (1917-1999), a budding composer and conductor. Alice and Wolf Strauss, refugees from Czechoslovakia, provided company and assistance when Margot Ruben lacked time. But more importantly Wolfskehl–through Denis Glover–came into contact with writers in Auckland. For about two years between 1942 and 1944 Wolfskehl played an active part in the cultural life of Auckland. By chance he passed Ronald Holloway’s Auckland print shop and found in him a likeminded spirit. He befriended Frank Sargeson–for a while a regular visitor and reader to Wolfskehl, R. A. K. Mason and A.R.D. Fairburn–who dedicated his volume Poems 1929-1941 (1943) to his refugee friend. What brought these younger writers to Wolfskehl was his openness and the interest he took in their work. He fascinated them with his wide and first-hand knowledge of contemporary European literature, as someone who knew and had conversed with literary figures they admired, such as Rilke, Thomas Mann and Kafka. In Wolfskehl they revered, as Sargeson wrote in his memoirs, ‘a great living representative of the European humanities’[29].

In spring 1942 Wolfskehl and Margot Ruben were able to rent a house not far away from where they had stayed in Mt Eden. This allowed them to receive their friends much more freely. Unfortunately, this lasted only for a year, after which they were forced to move out, ending a period of lively and inspiring interchange with a diverse range of literary, non-literary people and fellow refugees. It was their best time in Auckland. In the ensuing years Wolfskehl and Margot Ruben couldn’t find suitable accommodation where they could live together. They remained, however, always in close contact, even when from 1943 Wolfskehl had to live as a boarder. For a few weeks he stayed with Georg Tinter and his wife at their chicken farm in Henderson, then he moved to a room Frank Sargeson found for him in Takapuna. The unrest these changes caused affected his health and he had to go into a rest home for several months to recover. Later he found several accommodations in Mt Eden, mostly not very suitable, but he learnt to bear his fate and diminishing funds with stoic and black humour, as his letters testify.

These increasingly restrictive external circumstances, his growing blindness and reoccurring health issues impacted on his creativity. New poems only came occasionally, amongst them some of the moving love poems Flöten im Sturm (Flutes in the Storm) for Margot Ruben. He continued with drafts, corrections and addenda in his notebooks and eagerly followed Ernst Morwitz’s[30] American translation of Stefan George’s poetry into English. Through his regular visitors who came and read to him he also over the years acquired a good knowledge of modern English and American poets, such as Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, Hart Crane, W. H. Auden and Stephen Spender, whose works had previously been unknown to him.

When it became clear that the Allies would defeat Germany Wolfskehl felt relieved and began looking forward to what the victory would bring for the world, for him, and his work. The prospect of peace also inspired his creativity again. In 1944/5 he composed his crowning work, the cycle Hiob oder Die Vier Spiegel (Job or The Four Mirrors). In these poems Wolfskehl gave, as he wrote to Leo Baeck, his ‘vision of the essence of Judaism’[31], the Jewish people and its history up to the present. He completed the cycle Mittelmeer or Die Fünf Fenster (Mediterranean or The Five Windows), and made final alterations to the cycle INRI or The Four Tafeln (INRI or The Four Tablets) and to the ‘Lebenslied’ (Life Song) An die Deutschen (To the Germans).

With the end of the war and the lifting of mail restrictions Wolfskehl’s correspondence swelled considerably. He could now exchange a few letters with his wife Hanna before she died in spring 1946, and he learnt that his brother had perished in a concentration camp. Although he hoped to travel, at least temporarily, to Europe, he didn’t wish to return to Germany after what had happened to the Jews and the horrific extent of the Shoah had become known to the world. These plans, however, all evaporated, because of lack of money and a passport. After his naturalisation in July 1946 his health was too fragile to allow a long sea voyage.

In his final years Wolfskehl arranged and prepared an edition of his poetic work since 1933 under the title Die drei Welten (The Three Worlds) which had formed his identity–the Jewish, the German and the Mediterranean heritage. He planned smaller separate editions of the two works which were closest to his heart: the Job-cycle and To the Germans. Yet his publisher instead reissued in 1947 in New York a German-English edition[32] of Wolfskehl’s most successful collection Die Stimme spricht under the title 1933, marking the significance of that date for the Jews in Europe which had found expression in these poems. And friends in Switzerland found a publisher there who printed the poem An die Deutschen in a carefully designed edition of which a number of copies found their way to Germany. Both publications gave him joy and hope that his almost forgotten work would survive the catastrophe of Europe’s destruction and find new readers again.

1945, Bettina Photography, On a Roof to Terrace, courtesy, F. Voit.

In late 1947 and early 1948 Wolfskehl composed his last poem sequence, the Satyrspiel (Satyr Play). In this sarcastic summary and comment on post war realities, which remained unfinished, he also sharply criticises former friends who had sympathised with Nazi ideology and praised those who had remained true to their values like the writer Ricarda Huch or the two Stauffenberg brothers, followers of Stefan George, who had failed in their attempt to assassinate Hitler in 1944. Some of the poems he had written around New Year when he, together with Margot Ruben, spent a few relaxing days at the house of their friend Dorothea Beyda, the partner of R. A. K. Mason, and celebrated the turn of the year with a few New Zealand friends and a rare, at that time, bottle of New Zealand Riesling which turned, as one participant recalled, an ‘often just trivial routine into a very moving ceremony’[33].

Shortly afterwards, Wolfskehl fell ill with pneumonia, from which he seemed to have recovered, when an old intestinal illness recurred. After a few weeks in a private hospital paid for by German and New Zealand friends, Wolfskehl died on June 30, 1948. He is buried in Waikumete Cemetery, where a stone plaque engraved with his name in Hebrew and German and the Latin inscription ‘Exul Poeta’, together with a now tall cypress tree, marks his grave. He had assigned Margot Ruben as his literary heir, a task which she devotedly pursued in the following years to. In 1950 she published Hiob oder Die Vier Spiegel, followed in 1959 by the first collection of Wolfskehl’s letters written in New Zealand,[34] which showed him as one of the outstanding letter writers of his time. With the two-volume edition of Gesammelte Werke (Collected Works) in 1960, she achieved Wolfskehl’s literary return to Germany and firmly re-established his place in German Literature––as he had hoped for, and was convinced that he would attain, with the poetry written in his years of exile: ‘My fame ends in the harbour of Auckland, but it begins too in the harbour of Auckland.’[35]

Abbreviations and Bibliography:

BaN Karl Wolfskehls Briefwechsel aus Neuseeland 1938-1948. Ed. Cornelia Blasberg. 2 Vol. Darmstadt 1988

BfdK Blätter für die Kunst I-XIII. Ed. C. A. Klein. Berlin 1892-1919

BuA Briefe und Aufsätze. Ed. M. Ruben. München 1966

DLA Deutsches Literaturarchiv (German Literary Archive), Marbach

GW I/II Gesammelte Werke. Ed. M. Ruben and C. V. Bock. Hamburg 1960

SW Stefan George, Sämtliche Werke in 18 Bänden. Stuttgart 1982ff.

W/V Wolfskehl und Verwey. Die Dokumente ihrer Freundschaft 1897-1946. Ed. M. Nijland-Verwey. Heidelberg 1968

Footnotes:

1 The first line from Stefan George’s sixth ‚Jahrhundertspruch‘ (SW Bd. VI/VII, S. 183: ‘Nur aus dem fernsten her kommt die erneuung –) was for Wolfskehl a motto he used to quote at key turning points in his life.

2 This essay is a slightly abbreviated introduction to the anthology: Karl Wolfskehl, Three Worlds / Drei Welten. Selected Poems. German and English, translated and edited by Andrew Paul Wood and Friedrich Voit. Cold Hub Press: Lyttelton 2016

3 Evening Post (Wellington), 23 June 1938, p. 9.

4 To Gerda Eichbaum-Bell 29.1.38 (BaN p. 47f.).

5 To R. Italiener 13.6.46 (BaN p. 787).

6 GW II, p. 351-355

7 Wolfskehl told Margot Ruben that he had written the poem ‘Im Abendschatten’ (GW I, 52) when he was 18 (Margot Ruben, Gespräche und Aufzeichnungen 1934-1938. In: Karl Wolfskehl: Kalon Bekawod Namir. »Aus Schmach wird Ehr«. Amsterdam 1960, p. 109.

8 To Werner Bock 5.2.1947 (BaN 965).

9 Cf. Karl Wolfskehl, Begegnung mit Stefan George (1928); in: BuA p. 186.

10 Christopher Vernon Hassall in his biography of Rupert Brooke (1887-1915) give a detailed and amusing description of such a jour fixe at Wolfskehl’s house; cf. Rupert Brooke: A Biography. London 1964, S. 252 f.

11 To the M. Buber inspired and influential essay collection Vom Judentum (About Judaism; 1913) Wolfskehl contributed the introductory essay ‘Das Jüdischen Geheimnis’ (About the Jewish Secret, GW II, pp. 395-397).

12 Cf. to Verwey 13.12.1921 (W/V p. 161).

13 An extended collection of Wolfskehl’s prose writing can be found in GW II, pp. 184-556.

14 Benjamin, Walter: ‚Karl Wolfskehl zum sechzigsten Geburtstag. Eine Erinnerung.‘ In: Angelus Novus. Ausgewählte Schriften. Bd. 2. Frankfurt 1966, pp. 413-15.

15 Wolfskehl already knew the village where he had holidayed in earlier years, as in 1914 with Stefan George, a visit reflected in the poems ‘Der Brunnen’, ‘Die Kuppe’, ‘Die Bucht’.

16 Cf. GW II, pp. 158-167

17 New Zealand Herald (Auckland), July 4, 1938

18 The racial laws adopted in Italy in July and November 1938 decreed, inter alia, that all Jews who had come to Italy after 1919 had to leave the country within six months.

19 Cf. to G. Eichbaum 29.1.38 (BaN p.48).

20 Cf. to Morwitz 12.7.40 (BaN p. 384).

21 GW II, p. 179

22 GW II, p. 172-176.

23 Cf. Phoebe Meikle’s recollections about her friendship with Wolfskehl in Accidental Life. Auckland 1994

24 Wolfskehl’s censorship file survives in the National Archive and gives a revealing insight into the censor’s activity.

25 Otti Binswanger published a remarkable collection of stories And How Do You Like This Country (Wellington 1945; republished Auckland 2010) which gives an outsider’s impression of New Zealand in the 1940s.

26 Gert Christeller, to whom Wolfskehl dedicated a short poem (GW I, 267f.) later taught German at Victoria University, and Peter Munz was for many years history professor at the same university.

27 Cf. the poem ‘To the Creator of »Fantastica«.

28 The world premiere of this choral work took place many years later in 2014 in Wellington (http://www.richardfuchs.org.nz/).

29 More Than Enough. A Memoir (Auckland 1975, p. 112.

30 Ernst Morwitz (1887-1971), a friend of Stefan George and Karl Wolfskehl, had emigrated to the USA where he (together with Carol North Valhope) published his first translations in 1943.

31 To Leo Baeck 2.8.46 (BaN p.873).

32 The poems were translated by the George-translators, Ernst Morwitz and Carol North Valhope.

33 Phoebe Meikle, Accidental Life, p. 169.

34 Zehn Jahre Exil. Briefe aus Neuseeland 1938 – 1948. Heidelberg / Darmstadt 1959.

35 ‘Mein Ruhm endet im Hafen von Auckland, aber er beginnt auch im Hafen von Auckland.’ (Notebook No. 7, p. 112; dated: ‘11.VII.[19]47’; DLA).